The Ironclad Agreement? A Legal and Operational Analysis of the U.S. Arms Export Control Act and End-Use Monitoring

Table of Contents

The transfer of sophisticated military hardware from the United States to foreign nations is governed by a dense and multifaceted legal framework designed to balance the competing imperatives of foreign policy, national security, and international stability. This architecture is not merely a set of administrative hurdles; it is a deliberate system intended to ensure that U.S.-origin defense articles are used in a manner consistent with American interests and values. At the heart of this system lies the Arms Export Control Act (AECA), a foundational piece of legislation that provides the authority and the guiding principles for all U.S. defense trade. Understanding this statutory bedrock is essential to comprehending the stringent conditions, such as End-Use Monitoring (EUM), that are attached to the transfer of high-value assets like the F-16 fighter jet.1

I. The Statutory Architecture of U.S. Arms Exports#

A. The Arms Export Control Act (AECA): Purpose, Authority, and Foreign Policy Objectives#

Enacted in 1976, the Arms Export Control Act serves as the primary legal authority for the U.S. government to regulate the export and import of defense articles and services.2 The stated purpose of the Act is to further “world peace and the security and foreign policy of the United States”.3 This dual mandate establishes the AECA as both an instrument of foreign policy—enabling the U.S. to support its allies and partners—and a critical mechanism of national security, aimed at preventing sensitive military technology from falling into the wrong hands or being used in ways that destabilize regions or contravene U.S. interests.2

The core of the Act’s power resides in Section 38 (22 U.S.C. 2778), which grants the President of the United States the explicit authority to control arms exports.4 This presidential authority is not exercised in a vacuum. Through Executive Order 13637, this power is delegated to the Secretary of State, who is charged with the “continuous supervision and general direction” of all sales, leases, and exports of defense articles and services.4 This delegation is a crucial structural choice, placing the ultimate authority for arms transfers within the diplomatic apparatus of the U.S. government. It ensures that every proposed transfer is evaluated through a foreign policy lens, weighing its potential impact on bilateral relationships, regional balances of power, and overarching strategic goals. The Department of State, therefore, becomes the gatekeeper, ensuring that military-to-military cooperation aligns with the nation’s broader diplomatic posture.

The AECA codifies a specific risk assessment framework that must be applied to any potential arms sale. The Act mandates that any decision to issue an export license must take into account whether the transfer “would contribute to an arms race, aid in the development of weapons of mass destruction, support international terrorism, increase the possibility of outbreak or escalation of conflict, or prejudice the development of bilateral or multilateral arms control or nonproliferation agreements”.5 This language creates an inherent and perpetual tension within U.S. policy. On one hand, the Act is designed to facilitate “international defense cooperation” by arming allies for legitimate self-defense; on the other, it demands a rigorous evaluation of how those same arms could fuel conflict.5 This statutory paradox means that the executive branch is in a constant state of balancing the strategic benefits of a sale against the potential security and legal risks. For example, the sale of F-16s to Turkey is intended to bolster the capabilities of a key NATO ally, yet it simultaneously provides the very tools that have been used in ways that create friction with another NATO ally, Greece.6 The AECA does not resolve this tension but rather institutionalizes it, forcing a case-by-case analysis where policy priorities must be weighed against statutory risk factors.

The historical context of the Act is also revealing. The AECA of 1976 was an amendment and a renaming of the Foreign Military Sales Act (FMSA) of 1968.7 This change occurred in the political climate of the post-Vietnam War era, which was characterized by a strong desire within Congress to reassert its authority over foreign policy and national security matters, particularly the sale of arms abroad. This legislative history explains the Act’s robust mechanisms for congressional review and oversight, which were designed to act as a check on the executive branch’s authority and ensure a greater degree of accountability in the arms transfer process.5

B. The International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) and the U.S. Munitions List (USML)#

While the AECA provides the broad legal authority, the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR), found in Title 22 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR), Parts 120-130, provide the detailed implementation framework.2 The ITAR is the operational rulebook for U.S. defense trade, administered by the Department of State’s Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC) within the Bureau of Political-Military Affairs.8 It translates the statutory mandates of the AECA into specific requirements for registration, licensing, and compliance for any entity involved in the manufacture or export of defense articles.

Central to this regulatory scheme is the United States Munitions List (USML). The AECA authorizes the President to designate which items are to be considered “defense articles” and “defense services,” and this compilation is the USML.2 An item’s inclusion on the USML is the jurisdictional trigger that subjects it to the stringent controls of the ITAR. The USML is organized into 21 categories, which cover a vast range of military hardware, services, and technology.2 For instance, Category I covers firearms and ammunition, while Category VIII, “Aircraft and Related Articles,” is where advanced platforms like the F-16 fighter jet and its components are listed.2 The list also includes less tangible but equally critical items, such as technical data, which is essential for the operation, maintenance, and production of defense articles. The control of technical data is a critical aspect of the ITAR, preventing the unauthorized transfer of sensitive U.S. know-how to foreign nationals, even within the United States.2

C. Key Actors: The Roles of the President, Department of State, and Department of Defense#

The administration of the U.S. arms export control system is a complex interagency process, with distinct roles and responsibilities assigned to different branches of the executive.

The President and the Department of State (DoS): As the authority delegated by the President, the Secretary of State holds the ultimate responsibility for supervising and directing all defense trade.9 This authority is executed through the Bureau of Political-Military Affairs (PM) and its subordinate Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC). The DDTC is the primary licensing authority for Direct Commercial Sales (DCS) and is responsible for developing, updating, and enforcing the ITAR.8 The PM Bureau’s Office of Regional Security and Arms Transfers (PM/RSAT) plays a crucial role by conducting legal reviews of every proposed transfer to ensure it complies with the requirements of the AECA and the Foreign Assistance Act (FAA).10 This structure firmly embeds arms transfer decisions within the U.S. diplomatic and foreign policy establishment.

The Department of Defense (DoD): The DoD’s primary role in this process is the administration of the government-to-government Foreign Military Sales (FMS) program. This function is managed by the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA).7 The DSCA acts as the intermediary between the foreign customer and the U.S. defense industry, managing the entire lifecycle of an FMS case from the initial request to final delivery and closure. The detailed procedures for this process are laid out in the DSCA’s Security Assistance Management Manual (SAMM).11 Beyond its administrative role in FMS, the DoD also provides essential technical, security, and military expertise to the State Department during the review of all major arms sales, assessing factors such as technology security, interoperability with U.S. forces, and the partner nation’s ability to properly secure and employ the equipment.12

The delegation of ultimate authority to the State Department institutionalizes a “diplomatic-first” approach. While the DoD manages the mechanics of FMS, its role is subordinate to the broader foreign policy objectives determined by the State Department. This structure explains why political and diplomatic considerations often become central to arms sales negotiations. The potential sale of F-16s to Turkey, for instance, became explicitly linked to Turkey’s ratification of Sweden’s NATO membership.13 This linkage was possible because the transfer was not viewed merely as a military procurement but as a powerful piece of diplomatic leverage, a dynamic enabled by the AECA’s delegation of authority to the chief diplomatic officer of the United States.

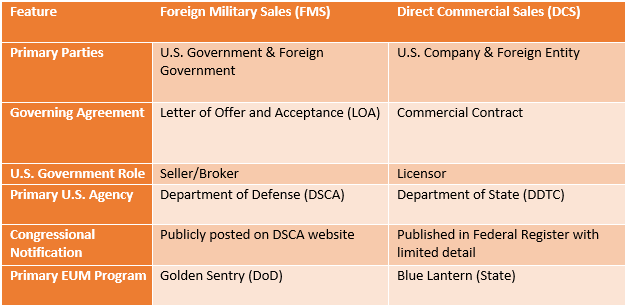

D. Channels of Transfer: A Comparative Analysis of Foreign Military Sales (FMS) and Direct Commercial Sales (DCS)#

The U.S. government facilitates arms transfers through two primary channels: Foreign Military Sales (FMS) and Direct Commercial Sales (DCS). The choice of channel has significant implications for the nature of the agreement, the level of U.S. government involvement, and the degree of public transparency.

Foreign Military Sales (FMS): FMS transactions are government-to-government agreements in which the U.S. government procures defense articles and services from U.S. industry on behalf of a foreign partner.2 This channel is typically used for the sale of major weapon systems, such as the F-16, as it allows the recipient nation to leverage the DoD’s vast acquisition, logistics, and program management expertise. A key feature of the FMS system is the “Total Package Approach,” which ensures that the sale includes not just the primary platform but also all necessary training, spare parts, logistical support, and munitions required for the recipient to field a complete and sustainable military capability.14

Direct Commercial Sales (DCS): DCS transactions are sales conducted directly between a U.S. defense company and an eligible foreign government or entity.15 In a DCS case, the U.S. government is not a party to the contract. However, it retains absolute control over the transaction through the licensing process. The U.S. company must obtain an export license from the State Department’s DDTC before any defense article, service, or technical data can be transferred.15 Proposed DCS sales are subject to the same AECA foreign policy and national security criteria as FMS cases, and major sales must also undergo the same congressional notification and review process.15

The distinction between these two channels is critical for oversight. FMS cases are generally more transparent, as the DSCA publicly posts the formal congressional notifications on its website, providing details on the equipment, cost, and justification for the sale.16 In contrast, while major DCS licenses are also notified to Congress, the public notification is limited to a quarterly publication in the Federal Register, which typically contains only boilerplate language and lacks the detail of FMS announcements.16 This “transparency gap” means that a significant portion of U.S. arms transfers, often exceeding FMS in total dollar value, occurs with substantially less public scrutiny.

Table 1: Comparison of Foreign Military Sales (FMS) and Direct Commercial Sales (DCS)#

II. The Transfer Process: From Request to Delivery#

The journey of a defense article like an F-16 from a U.S. production line to a foreign air force is a long and highly regulated process, marked by numerous legal and administrative checkpoints. This process is designed to ensure that every transfer is properly vetted, authorized, and structured to uphold U.S. law and policy. Central to this lifecycle are the binding agreements that codify the recipient’s obligations and the robust system of congressional oversight that provides a crucial check on executive authority.

A. The Letter of Offer and Acceptance (LOA): Anatomy of a Government-to-Government Agreement#

For transfers conducted through the FMS channel, the Letter of Offer and Acceptance (LOA) is the cornerstone of the entire transaction. It is the formal, legally binding, government-to-government agreement that details the precise defense articles, services, and training to be provided; the estimated costs and payment schedule; and the comprehensive terms and conditions that the recipient nation must accept.17 The LOA is a unique legal instrument, developed under the authority of the AECA and governed by the policies of the SAMM, not by standard U.S. procurement laws like the Federal Acquisition Regulation (FAR).18

The process is initiated when a partner nation submits a formal Letter of Request (LOR) to the U.S. government, outlining its military requirements.17 In response, the relevant U.S. Military Department, in coordination with the DSCA, develops the LOA. This document constitutes a formal offer from the U.S. government, which remains valid until a specified Offer Expiration Date (OED).18 A foreign government accepts the offer by having an authorized representative sign the LOA and submitting the required initial financial deposit.17 This acceptance transforms the LOA into a binding FMS case, providing the U.S. government with the authority to procure the requested items from industry or provide them from its own stocks. For major systems, this process can be exceedingly complex and lengthy, often taking many months or even years from the initial LOR to the final implementation of the case.17

B. The “Total Package Approach”: Integrating Training, Logistics, and Sustainment#

A hallmark of the U.S. FMS system is the “Total Package Approach” (TPA). This policy ensures that the sale of a major weapon system is not merely a transfer of hardware but a comprehensive delivery of a full-spectrum military capability.14 When a nation acquires F-16s through FMS, the LOA will typically include not only the aircraft themselves but also all the necessary ancillary elements required for their effective operation and sustainment. This includes pilot and maintenance training, technical assistance from U.S. personnel, ground support equipment, initial stocks of spare parts, and a full complement of compatible munitions and weapon systems.14

This holistic approach serves two primary purposes. First, it ensures that the recipient nation has the institutional capacity to properly absorb, operate, and maintain the sophisticated technology it is acquiring, thereby maximizing the strategic benefit of the transfer for both the U.S. and the partner.14 Second, and perhaps more critically from a strategic perspective, it establishes a long-term logistical and technological relationship between the United States and the recipient nation. An advanced aircraft like the F-16 requires a continuous supply chain of specialized spare parts, frequent software updates for its mission systems and avionics, and ongoing access to U.S. technical expertise.19 By providing these elements as part of the initial sale, the U.S. creates a state of logistical dependency. This dependency serves as a powerful, non-statutory form of leverage. If a recipient nation were to violate the terms of the transfer agreement, the U.S. could threaten to restrict or cut off the flow of sustainment support, a move that would, over time, render the recipient’s entire F-16 fleet inoperable.19 This practical leverage is often a more flexible and potent tool for influencing a partner’s behavior than the formal legal penalties prescribed in the AECA. The suspension of F-16 deliveries to Israel by the Reagan administration in 1982 serves as a historical example of this tool being used to achieve a specific foreign policy objective.20

C. The Role of Congress: Statutory Notification, Review, and Political Leverage#

Congress plays a powerful role as a check on the executive branch’s authority to sell arms. The AECA establishes a formal process of congressional notification and review for all major arms transfers, whether through FMS or DCS.15

For a proposed sale of Major Defense Equipment like F-16s, the Act sets specific monetary thresholds that trigger this requirement. For most countries, the threshold is $14 million. For a designated list of close allies—including NATO members, Japan, Australia, South Korea, Israel, and New Zealand—the threshold is raised to $25 million.21 Once the executive branch determines it intends to proceed with a sale exceeding these thresholds, it must formally notify Congress. This initiates a statutory review period of 30 calendar days for most countries, or 15 days for the specified allies.21 During this window, Congress has the authority to pass a joint resolution of disapproval to block the sale. However, this is a very high bar to clear. Such a resolution would require majority support in both the House and the Senate and would almost certainly face a presidential veto, which would in turn require a two-thirds majority in both chambers to override. Consequently, a joint resolution of disapproval has never been successfully used to block a proposed arms sale.21

The true power of congressional oversight, however, lies not in this formal statutory process but in a well-established, non-statutory informal review process. By long-standing practice, the State Department provides a preliminary, confidential notification of a potential major arms sale to the chairs and ranking members of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and the House Foreign Affairs Committee.21 This “tiered review” occurs between 20 and 40 days before the formal notification is sent and the statutory clock begins to tick. During this informal period, committee leaders and their staffs can review the proposed sale, ask questions, and raise concerns directly with the State Department. Crucially, a member can place an informal “hold” on the sale. While not legally binding, these holds carry immense political weight. The State Department has a general policy of not proceeding with a formal notification if a significant congressional concern, manifested as a hold, is in place.21 This informal process effectively gives a small number of influential lawmakers a de facto veto over major arms sales, allowing them to halt a multi-billion-dollar transfer behind closed doors. This is where the real negotiation and exercise of congressional leverage occurs, enabling lawmakers to extract concessions from the administration or link approval of a sale to unrelated policy matters, as was clearly demonstrated by the conditioning of the F-16 sale to Turkey on its approval of Sweden’s NATO membership.13

D. Recipient Obligations: Binding Commitments on Use, Security, and Non-Transfer#

Every arms transfer agreement concluded under the authority of the AECA contains a core set of binding commitments that the recipient nation must legally agree to uphold. These obligations are the foundation of the end-use control regime and apply for the entire operational life of the defense article. The three fundamental tenets are:

Restrictions on Use: The recipient country must agree to use the defense articles solely for the purposes for which they were provided.22 These purposes are generally defined in the AECA as “internal security” and “legitimate self-defense”.5 The Act does not provide precise definitions for these terms, leaving them open to interpretation, which can become a point of contention, particularly when U.S.-supplied weapons are used in conflicts with significant civilian casualties.5

Security Requirements: The recipient must agree to maintain the physical security of the defense articles and provide a degree of protection that is “substantially the same” as that afforded to such articles by the U.S. government itself.10 This is intended to prevent the equipment from being lost, stolen, or compromised, and to protect the sensitive technology embedded within it.

Prohibition on Third-Party Transfer: The recipient nation must agree not to transfer title to, or possession of, the defense article to any third party—whether another country, an international organization, or a non-state actor—without first obtaining the prior written consent of the U.S. government.10 This is one of the most critical restrictions, designed to prevent the uncontrolled proliferation of U.S. military technology.

These three commitments form the legal basis for the End-Use Monitoring program. They are not mere suggestions but legally binding conditions of the sale. A violation of these terms constitutes a breach of the agreement and can trigger the enforcement mechanisms detailed later in this blog.

III. End-Use Monitoring: The Cornerstone of Accountability#

The commitments made by a recipient nation at the time of transfer are not based on an honor system. The U.S. government has established a comprehensive and legally mandated framework to verify compliance with these obligations throughout the lifecycle of the defense articles. This framework, known as End-Use Monitoring (EUM), is the cornerstone of the AECA’s accountability regime. It is designed to provide the U.S. government with a mechanism to ensure that its military technology is being used, secured, and controlled in accordance with the terms of the transfer agreement and U.S. law.

A. Section 40A of the AECA: The Legal Mandate for EUM#

The requirement for a formal EUM program is not merely a matter of policy; it is enshrined in law. Section 40A of the Arms Export Control Act (22 U.S.C. 2785) explicitly directs the President to establish and implement a program for the end-use monitoring of all defense articles and services sold, leased, or exported under the AECA or the Foreign Assistance Act.11

The stated purpose of this statutory mandate is twofold. First, it is to “improve accountability” with respect to U.S.-origin defense articles.23 Second, it is to provide “reasonable assurance” that the recipient nation is complying with the requirements imposed by the U.S. government regarding the use, transfer, and security of the items.11 The program is intended to serve as a practical tool to detect and deter the diversion of sensitive technology or the misuse of U.S. weaponry, thereby protecting both U.S. national security interests and the technological edge of American warfighters.23 The law also requires an annual report to Congress on the implementation of the EUM program, including a detailed accounting of its costs and personnel.24

B. The “Golden Sentry” Program: DoD’s Monitoring of FMS Transfers#

In response to the mandate of Section 40A, the Department of Defense established the “Golden Sentry” program to conduct EUM for all defense articles and services transferred through the government-to-government FMS system.15 The program is administered by the Defense Security Cooperation Agency (DSCA) and is implemented in-country by the Security Cooperation Organizations (SCOs) located at U.S. embassies worldwide.12

A key principle of the Golden Sentry program is that monitoring is a joint responsibility shared between the U.S. government and the partner nation.11 As a condition of the sale, the recipient country must agree to permit U.S. representatives to observe the use of the articles and must furnish any necessary information upon request.22 The SCOs, as the on-the-ground representatives of the DoD, are responsible for coordinating with the host nation’s military to conduct the physical checks and inventories required by the program.

C. The “Blue Lantern” Program: State Department’s Oversight of Commercial Sales#

Parallel to the DoD’s Golden Sentry program, the Department of State operates the “Blue Lantern” program to monitor defense articles and services transferred through Direct Commercial Sales (DCS).15 Administered by the Directorate of Defense Trade Controls (DDTC), the Blue Lantern program is the U.S. government’s first systematic EUM program, initiated in 1990 and codified into law in 1996.25

The primary function of the Blue Lantern program is to conduct verification checks to confirm the legitimacy of the parties and the stated purpose of a commercial transaction.26 These checks can occur at three stages: pre-license, to vet unfamiliar foreign companies before a sale is approved; post-license but pre-shipment, to confirm details before the items leave the U.S.; and post-shipment, to verify that the items arrived at the correct destination and are being used as intended.26 Blue Lantern checks are not law enforcement investigations but rather compliance reviews designed to mitigate the risk of diversion and combat the “gray arms” trade, where legitimate channels are used to fraudulently acquire weapons for unauthorized re-transfer.26 A foreign entity’s lack of cooperation with a Blue Lantern check can result in increased scrutiny or the denial of future export licenses.26

The existence of two separate EUM programs, run by two different executive departments, creates a potential for administrative complexity and coordination challenges. Golden Sentry is managed by the DoD’s security cooperation enterprise, focused on FMS partners, while Blue Lantern is managed by the State Department’s regulatory and licensing arm, focused on commercial compliance. This bifurcation can lead to confusion and monitoring gaps, particularly in cases where a partner nation receives U.S. equipment through a mix of FMS and DCS channels. A Government Accountability Office (GAO) report on U.S. assistance to Guatemala highlighted this very issue, finding that night vision devices that should have been monitored under the State Department’s Blue Lantern program were being inaccurately tracked within the DoD’s Golden Sentry system, demonstrating how this administrative division can compromise the integrity of the monitoring process.27

D. A Tale of Two Tiers: Differentiating Routine vs. Enhanced End-Use Monitoring (EEUM)#

Recognizing that it is not feasible to apply the most stringent level of monitoring to every piece of equipment transferred, the Golden Sentry program employs a two-tiered, risk-based approach: Routine End-Use Monitoring (REUM) and Enhanced End-Use Monitoring (EEUM).

Routine EUM (REUM): This is the baseline level of monitoring that applies to the vast majority of defense articles sold via FMS.12 REUM is a less formal process, typically involving observations conducted by SCO personnel in the course of their other regular duties, such as during visits to partner nation military installations or training exercises.28 The focus of REUM is on a “watch list” of significant military equipment, which includes broad categories such as battle tanks, armored combat vehicles, large-caliber artillery systems, and military fixed-wing aircraft and helicopters.28 SCOs are required to document these observations in quarterly reports.29

Enhanced EUM (EEUM): This is a much more rigorous and intrusive monitoring regime reserved for defense articles that are deemed to incorporate highly sensitive technology, are particularly vulnerable to diversion or misuse, or whose compromise could have significant negative consequences for U.S. national security.11 The principle of EEUM is “trust with verification”.12 Items designated for EEUM include man-portable air defense systems (MANPADS) like the Stinger missile, advanced anti-tank missiles like the Javelin, night vision devices, and sophisticated beyond-visual-range air-to-air missiles such as the AMRAAM.12

This tiered system represents a pragmatic allocation of finite monitoring resources. However, the effectiveness of the lower tier, REUM, is a significant concern. While EEUM is defined by clear, verifiable metrics like 100% serial number inventories and formal physical security checks, REUM is based on “casual observation” and “opportune” sources of information.12 This unstructured approach makes its effectiveness highly dependent on the diligence and opportunities of individual SCO personnel. The GAO’s finding that even these basic routine checks were not consistently completed in its review of Northern Triangle countries suggests that a vast category of U.S.-supplied military equipment is subject to a monitoring regime that may be weak in both its design and its implementation.27 This creates a potential for a significant portion of U.S. arms transfers to receive only nominal oversight.

IV. Enhanced Monitoring in Practice: The F-16 Case Study#

The general principles of End-Use Monitoring become tangible when applied to a specific, high-value asset like the F-16 Fighting Falcon. As an advanced, multi-role tactical aircraft, the F-16 and its associated systems embody the precise characteristics of sensitive technology and strategic importance that trigger the most stringent monitoring requirements. An examination of how Enhanced End-Use Monitoring (EEUM) would be applied to an F-16 fleet illustrates the depth and complexity of the U.S. commitment to safeguarding its defense technology post-transfer.

A. Designating an Asset for EEUM: Technology Sensitivity and Diversion Risk#

The decision to subject an item to EEUM is based on a risk assessment that considers its technological sophistication, its vulnerability to diversion or theft, and the potential consequences of its compromise.11 While military fixed-wing aircraft as a general category are on the watch list for Routine EUM, the F-16, particularly its modern variants and advanced subsystems, would undoubtedly meet the criteria for the enhanced regime.28

The aircraft itself, along with its powerful engine, advanced radar, electronic warfare suite, targeting pods, and mission computers, contains sensitive U.S. technology that is a prime target for reverse-engineering by adversaries. Furthermore, the F-16 is a platform for delivering some of the most advanced munitions in the U.S. inventory, such as the AIM-120 Advanced Medium-Range Air-to-Air Missile (AMRAAM) and the AIM-9X Sidewinder missile, both of which are explicitly designated for EEUM.24 Therefore, any FMS case involving F-16s would include specialized physical security and accountability notes, or provisos, written directly into the Letter of Offer and Acceptance (LOA), legally obligating the recipient nation to comply with the EEUM protocol.12

B. Initial and Annual Inventories: Serial Number Verification Protocols#

The central pillar of EEUM is the meticulous, physical inventory of every designated item, verified by its unique serial number.26 This process is far more demanding than a simple accounting audit; it is a hands-on verification designed to confirm the physical presence and integrity of the equipment.

Baseline Inventory: The process begins upon the arrival of the equipment in the recipient country. U.S. personnel from the in-country Security Cooperation Organization (SCO) are required to conduct an initial inventory, verifying the serial number of each EEUM-designated item within 90 days of delivery.30 For an F-16 program, this would involve physically inspecting each aircraft airframe, each engine, each targeting pod, and every single designated missile and guided bomb to record its serial number. This initial count establishes the baseline inventory against which all future checks will be measured.

Annual 100% Verification: Following the initial count, the SCO is required to conduct a 100% serial number inventory of all EEUM items at least once every year.26 This requires planned and coordinated visits to the partner nation’s military installations.24 For an F-16 fleet, this is a significant logistical undertaking. It means U.S. personnel must be granted access to active airbases, flight lines, maintenance hangars, and secure munitions storage facilities to physically locate and visually confirm the serial number of every single designated asset. The results of this inventory are then meticulously recorded in the central EUM database.

C. Physical Security and Accountability Assessments: Safeguarding the Asset#

Beyond simply counting the items, EEUM involves a thorough assessment of the physical security measures in place to protect them.26 The standard mandated by the transfer agreements is that the recipient nation must provide a degree of protection “substantially the same” as that afforded by the U.S. government.22

During their inventory visits, SCO personnel conduct physical security checks of the facilities where the F-16s and their associated equipment are stored, maintained, and operated. This includes inspecting the perimeter security of the airbase, the access controls for hangars and maintenance bays, and the specific security protocols for munitions storage areas (often referred to as “igloos” or bunkers). The objective is to ensure compliance with the technology control requirements outlined in the LOA and to minimize the risk of unauthorized access, theft, or espionage. A key concern is preventing third-country nationals from gaining access to the sensitive technology, a point of significant friction in the U.S.-Pakistan relationship due to Pakistan’s close defense ties with China.31

The intrusive nature of these requirements—demanding that a sovereign nation grant foreign officials regular access to its front-line military bases and sensitive operational procedures—inevitably creates a point of diplomatic and military friction. The DoD itself acknowledges its sensitivity to issues of sovereignty with its allies and the need to ensure these governments understand the legal mandate for EUM.12 This inherent tension is a likely contributor to the access issues that the U.S. cited in its 2019 reprimand to Pakistan, where it was noted that U.S. officials had been prevented from performing security vulnerability assessments for a period of four years.32 The very design of EEUM, while necessary for accountability, establishes a persistent challenge to the bilateral relationship.

D. The Security Cooperation Information Portal (SCIP): The Digital Backbone of EUM#

The vast amount of data generated by the EUM program is managed through a centralized, secure IT system known as the Security Cooperation Information Portal (SCIP).22 The SCIP-EUM module serves as the sole authoritative repository and the official system of record for all EUM-related data and documentation, particularly the detailed inventories of EEUM items.22

SCO personnel are responsible for entering all baseline and annual inventory data into SCIP, including the serial numbers of each F-16 airframe, engine, and designated munition.30 The portal is also used to track the disposition of these items over time. If a missile is expended in a training exercise or in combat, or if an aircraft is lost in an accident, this information must be documented in SCIP to maintain an accurate inventory.24 The system provides a real-time, web-based platform that allows authorized users at the SCO, the regional Combatant Commands, the Military Departments, and the DSCA to view and manage EUM data, track compliance with annual inventory requirements, and generate reports.24

The entire “trust with verification” model of EEUM is critically dependent on the accuracy and integrity of the data within SCIP. The physical inventory is only meaningful if it is checked against a reliable and complete baseline record. However, GAO audits have identified significant weaknesses in this digital backbone. A 2022 report on the Northern Triangle countries found that the DoD’s data in SCIP was inaccurate, with conflicting information about which items were subject to EEUM and incomplete records.27 This finding points to a systemic vulnerability. If the foundational data in the official system of record is flawed, the entire EEUM process—from tracking F-16s to accounting for individual missiles—is compromised, creating a false sense of security and undermining the legal and operational objectives of the monitoring regime.

V. Breach and Consequence: The Enforcement Regime#

The terms and conditions attached to U.S. arms transfers are not merely aspirational; they are backed by a robust enforcement regime with a wide spectrum of potential consequences for non-compliance. When a recipient nation violates its agreements—whether by using weapons for an unauthorized purpose, failing to secure them properly, or transferring them to a third party without consent—the U.S. government has a range of tools at its disposal. These tools extend from formal legal and financial penalties to more pragmatic and often more powerful forms of diplomatic and logistical leverage. The application of these enforcement mechanisms, however, is rarely a simple matter of legal adjudication; it is almost always a complex calculation of foreign policy, strategic interests, and political will.

A. Identifying and Reporting Violations: From SCOs to the President and Congress#

The enforcement process begins with the identification and reporting of a potential violation. The U.S. government’s in-country personnel, particularly the members of the Security Cooperation Organization (SCO) at the U.S. Embassy, serve as the first line of detection. All DoD personnel are under a strict requirement to report any suspected end-use violation—including unauthorized access to technology, unapproved transfers, security breaches, or known equipment losses—through their chain of command.22 These reports are funneled to the DSCA and the Department of State, which are jointly responsible for investigating the allegations.22

Once a substantial violation is confirmed, the AECA imposes a direct obligation on the executive branch. Section 3(c)(2) of the Act requires the President to submit a report to Congress detailing any substantial violation of a transfer agreement, with a particular emphasis on any transfer made without the prior consent of the U.S. government.22 This statutory reporting requirement ensures that the legislative branch is formally apprised of significant breaches, creating a mechanism for congressional oversight of the enforcement process.

B. A Spectrum of Penalties: Civil Fines, Criminal Prosecution, and Debarment#

The AECA and its implementing regulations, the ITAR, provide the State Department with significant legal authority to impose penalties for violations. These penalties can be applied to individuals, companies, or even foreign government entities involved in the breach.

Civil Penalties: The Assistant Secretary of State for Political-Military Affairs is authorized to impose civil penalties, which typically involve substantial monetary fines.33 For each violation of the ITAR, civil fines can reach up to $500,000 or more.34 These penalties are often accompanied by a Consent Agreement, under which the violating party agrees to implement enhanced compliance measures to prevent future infractions.33

Criminal Penalties: In cases of “willful” violations, the Department of Justice can pursue criminal prosecution. A criminal conviction carries much stiffer penalties, including fines of up to $1 million per violation and potential imprisonment for individuals for up to 10 or 20 years.34

Administrative Actions and Debarment: For many entities, the most severe consequence is not a fine but an administrative sanction. The State Department has the authority to deny or revoke export privileges, effectively cutting off a company or a country from receiving any U.S. defense articles or services in the future.34 This “debarment” is a powerful tool, as it can cripple a foreign military’s ability to sustain its U.S.-origin equipment or acquire new capabilities.35

C. Diplomatic and Practical Leverage: The Power of Withholding Spares, Upgrades, and Support#

Beyond the formal legal penalties, the U.S. government’s most potent and frequently used enforcement tool is its practical control over the sustainment of the transferred equipment. As established by the “Total Package Approach,” advanced weapon systems like the F-16 are deeply dependent on a continuous logistical pipeline from the United States for spare parts, software updates, and technical support.36 This dependency creates a powerful “sustainment kill switch”.37

If a recipient nation engages in behavior that the U.S. deems a violation of its agreements, Washington can signal its displeasure or coerce a change in policy by simply slowing down or halting the flow of this critical support. This can range from delaying the delivery of a planned upgrade package to refusing to sell essential spare parts, a move that would eventually ground the recipient’s fleet. This form of leverage is often preferred to formal sanctions because it is more flexible, can be scaled to the severity of the infraction, and can be implemented without the political and diplomatic fallout of publicly declaring a strategic partner to be in violation of U.S. law. A clear historical precedent for this was set in 1982 when the Reagan administration temporarily suspended the delivery of F-16s to Israel to pressure its withdrawal from Lebanon, demonstrating the power of using the supply chain as a direct instrument of foreign policy.20

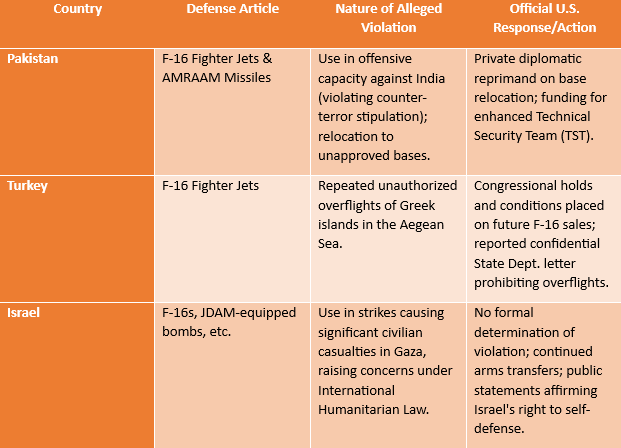

D. Case Studies in Non-Compliance#

The application of these enforcement tools is best understood through real-world examples. The U.S. response to alleged violations by key strategic partners—Pakistan, Turkey, and Israel—reveals a consistent pattern of prioritizing the preservation of the strategic relationship over the strict, punitive enforcement of the law.

Table 2: Summary of Selected End-Use Violation Cases and U.S. Responses#

Pakistan (2019): Alleged Misuse of F-16s and the U.S. Response

In the aftermath of an Indian airstrike in Balakot, Pakistan, in February 2019, the two nations engaged in an aerial dogfight over Kashmir. India presented evidence, including fragments of an AIM-120 AMRAAM missile, indicating that the Pakistan Air Force (PAF) had used its U.S.-supplied F-16s in the engagement.38 This raised immediate concerns that Pakistan had violated its end-use agreement, which stipulated that the aircraft were to be used for counterterrorism operations, not in offensive actions against a neighboring state.39

The official U.S. government response was publicly circumspect. The State Department acknowledged that it was “aware of these reports and are seeking more information”.40 However, behind the scenes, the U.S. took a more direct, albeit nuanced, approach. Leaked documents later revealed that in August 2019, the U.S. Under Secretary of State for Arms Control and International Security Affairs, Andrea Thompson, sent a formal letter of reprimand to the chief of the PAF.31 Interestingly, the letter did not directly address the use of the F-16s against India. Instead, it focused on a separate, more procedural violation: the U.S. had determined that Pakistan had moved its F-16s and their associated missiles to forward operating bases that were not authorized under the terms of the sale. The letter stated that this action was “concerning and inconsistent with the F-16 Letter of Offer and Acceptance” and raised concerns about the security of the sensitive U.S. technology.32 In addition to the diplomatic reprimand, the U.S. also moved to tighten its physical oversight, authorizing a $125 million FMS case to fund a “Technical Security Team” of 60 U.S. contractor representatives in Pakistan to assist in monitoring the F-16 program.31 This response was a clear example of calibrated enforcement: the U.S. addressed the breach and increased its monitoring presence without publicly accusing Pakistan of misusing the jets against India, an action that would have had far more severe diplomatic repercussions for the complex U.S.-Pakistan relationship.

Turkey: Aegean Overflights and Congressional Conditions

For decades, tensions between NATO allies Turkey and Greece have been marked by disputes over sovereignty in the Aegean Sea. A frequent manifestation of this tension has been the use of Turkish Air Force F-16s to conduct unauthorized overflights of inhabited Greek islands, a direct challenge to Greek sovereignty.41 These actions have been a persistent source of concern for U.S. lawmakers, who have questioned the wisdom of providing advanced weaponry to an ally that uses it to intimidate another.

The U.S. response to these actions has not come in the form of formal sanctions or penalties for past behavior. Instead, the primary leverage has been exerted by the U.S. Congress through its oversight of future arms sales. During the lengthy negotiations over Turkey’s recent request to purchase 40 new F-16s and modernization kits for its existing fleet, key members of Congress, particularly in the Senate Foreign Relations and House Foreign Affairs Committees, explicitly stated that their approval was contingent on Turkey ceasing its aggressive actions in the Aegean.13 This congressional pressure ultimately led the Biden administration to provide assurances as part of the approval process. According to credible diplomatic sources, the State Department sent a confidential letter to the relevant congressional committees stipulating that the sale was conditioned on Turkey not using the F-16s for overflights of Greek islands and that the program could be terminated if this condition were violated.42 This represents a forward-looking enforcement mechanism, using the leverage of a pending sale to shape future behavior rather than punishing past transgressions.

Israel: Use of U.S. Munitions and International Humanitarian Law Considerations

A third, and highly contentious, case involves the use of U.S.-supplied weapons by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) in its military operations in Gaza. The AECA requires that U.S. arms be used for “legitimate self-defense”.5 However, prominent human rights organizations, such as Amnesty International, have repeatedly documented Israeli airstrikes in Gaza that have killed large numbers of civilians. Their investigations have identified the use of U.S.-made munitions, including Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM) guidance kits that convert unguided bombs into precision weapons, in attacks that they assess were either indiscriminate or direct attacks on civilians and civilian objects, potentially constituting war crimes under international humanitarian law.43

Despite this extensive documentation from non-governmental organizations and various United Nations bodies 66, the U.S. executive branch has consistently maintained that Israel’s use of U.S. weapons falls within the scope of legitimate self-defense. No formal determination of an end-use violation has been made, and the flow of U.S. military assistance and arms transfers to Israel has continued. This has led to sustained calls from human rights groups for the U.S. to enforce its own laws and suspend arms transfers to Israel until it complies with international humanitarian law.44 This case highlights the profound influence of political and strategic considerations on the enforcement process. The deep strategic partnership between the U.S. and Israel, combined with strong political support within both the executive and legislative branches, has resulted in a situation where credible allegations of misuse have not triggered the formal enforcement mechanisms available under the AECA.

These case studies collectively demonstrate that the enforcement of the AECA is not a rigid, legalistic process but a highly politicized one. The U.S. government consistently calibrates its response to balance the legal requirements of the Act against the perceived imperatives of its strategic relationships. The “ironclad” legal agreement is, in practice, politically malleable, with the harshest penalties reserved for adversaries, while key partners are more likely to face quieter, more nuanced forms of pressure designed to modify behavior without rupturing the underlying partnership.

VI. A Critical Assessment: Systemic Challenges and the Efficacy of EUM#

While the End-Use Monitoring program represents a comprehensive effort to ensure accountability for U.S. arms transfers, it is not without significant systemic challenges and limitations. Independent assessments by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) and expert analysis from policy research organizations like the Stimson Center have identified critical gaps in the program’s design, implementation, and transparency. These critiques reveal a system that, while effective at tracking the physical custody of weapons, is ill-equipped to monitor their operational use and is increasingly shielded from public and congressional oversight.

A. Analysis of Government Accountability Office (GAO) Findings: Gaps in Timeliness, Data Integrity, and Scope#

As the investigative arm of Congress, the GAO has conducted numerous audits of the EUM program, consistently identifying significant deficiencies in its implementation.

Data Integrity and Accuracy: A recurring theme in GAO reports is the unreliability of the data within the Security Cooperation Information Portal (SCIP), the supposed authoritative database for EUM.22 A 2022 report examining U.S. assistance to the Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras found that the DoD’s data on which equipment was subject to Enhanced EUM was inaccurate and riddled with conflicting information. This led to a failure to conduct all required monitoring of sensitive equipment, as SCO personnel were working from a flawed baseline.27 If the foundational inventory data is incorrect, the entire verification process is compromised.

Failure to Meet Timeliness Standards: The GAO has also found that the DoD consistently fails to meet its own timeliness standards for conducting EUM checks. A 2019 report on security assistance to Lebanon revealed that nearly one-third of all required EEUM observations were delinquent.45 The report identified the cause as a systemic flaw in how the DSCA calculates inspection due dates, which does not take into account the date of the last inspection. This can result in some sensitive equipment going nearly two years between checks, undermining the program’s ability to ensure items are properly accounted for and safeguarded.45

Gaps in Policy and Scope: The GAO has also highlighted gaps in the scope of the EUM program itself. The 2022 Northern Triangle report found that the DoD lacked any documented policies for recording or investigating allegations of misuse for equipment that falls outside the formal Golden Sentry program. This was the case with a fleet of Jeeps provided to Guatemala, which were allegedly used to intimidate U.S. embassy officials. Because the Jeeps were not subject to Golden Sentry monitoring, there was no formal process to investigate the allegations.27 This reveals a significant loophole where certain categories of U.S.-provided equipment may be subject to no meaningful end-use oversight at all.

B. The “Custody vs. Use” Dilemma: Limitations of Monitoring Operational Conduct#

Perhaps the most fundamental critique of the EUM program is that it is designed primarily to verify the physical custody and security of defense articles, not to monitor how they are operationally used. This represents a profound disconnect between the program’s implementation and the legal requirements of the AECA.

The AECA obligates recipient nations to use U.S. weapons for “legitimate self-defense”.5 This is an explicit condition related to the use of the weapon. However, in its report on the Northern Triangle, the GAO found that DoD officials explicitly stated that the Golden Sentry program is “not designed to verify how recipients use equipment”.27 Instead, its focus is on confirming that the recipient has maintained physical control of the item and has implemented the required security protocols. This is a foundational design choice, not a mere implementation flaw. It means that the U.S. government can successfully verify that every F-16 in a partner’s inventory is securely stored at an approved airbase—thus fulfilling the operational goals of the EUM program—while having no formal mechanism within that same program to verify whether that F-16 was used in an airstrike that violated international humanitarian law, a potential breach of the underlying legal agreement.

This “custody vs. use” dilemma has profound implications for human rights. A 2024 GAO report on human rights and arms transfers found that existing agency processes are not sufficient to fully address the risk that U.S. defense articles may be used to commit human rights abuses.46 The report noted that the State Department’s process for responding to incidents of civilian harm, the Civilian Harm Incident Response Guidance (CHIRG), does not allow for the intake of reports from non-U.S. government sources, such as the United Nations or international NGOs.46 This severely limits the U.S. government’s visibility into potential violations. Because the EUM program is not designed to proactively monitor operational use, the DoD and State Department are left to rely on third-party reports from media or civil society to learn of potential misuse. Yet, the GAO found that officials had not even considered investigating credible allegations that it had identified from such public sources.27 This systemic gap has led to calls from organizations like the RAND Corporation for the development of a new “operational EUM” paradigm that would expand the scope of monitoring to include the actual employment of U.S.-origin weapons in combat.47

C. The Transparency Deficit: Insights from the Stimson Center on Public and Congressional Oversight#

Expert analysis from the Stimson Center, a non-partisan policy research organization, concludes that the U.S. arms trade is characterized by a dangerous and deepening lack of transparency. This opacity shields the arms transfer enterprise from meaningful oversight, analysis, and accountability, undermining efforts to ensure that sales are conducted responsibly.

Deteriorating Quality of Public Reporting: The Stimson Center finds that the quality and quantity of public reporting on U.S. arms sales have declined significantly in recent years. Official reports that once provided more detailed breakdowns have shifted to presenting highly aggregated figures, obscuring important trends and details.48 For example, the DSCA’s annual Historical Sales Book, a congressionally mandated report, no longer provides country-level detail for many Building Partner Capacity (BPC) military aid programs, instead consolidating them into a single, uninformative total.49

The Black Box of Direct Commercial Sales (DCS): A major transparency gap exists around DCS, which in recent years have accounted for more than half of all U.S. arms transfers by value.50 Unlike FMS notifications, which are publicly posted in detail on the DSCA website, congressional notifications for major DCS licenses are not made public in a similar manner. This means that billions of dollars in U.S. weapons exports are approved with minimal opportunity for public or legislative scrutiny before the fact.50

The U.S. government often defends this lack of transparency by citing the need to protect operational security (OPSEC) or the proprietary commercial information of U.S. defense companies.51 However, the Stimson Center argues that these justifications are frequently overstated. The high degree of transparency the U.S. has demonstrated regarding its massive arms transfers to Ukraine—a live conflict zone where OPSEC concerns are paramount—proves that greater disclosure is possible when the political will exists.48 The contrast between the detailed, regular updates on aid to Ukraine and the opacity surrounding sales to other partners suggests that the trend toward secrecy is a deliberate policy choice, not a security necessity. This choice has the effect of insulating the executive branch from accountability, lowering the political cost of approving controversial arms sales that might face significant opposition if they were subject to greater public scrutiny.50

D. Operating in Conflict Zones: The Unique Challenges of EUM in Hostile Environments#

The challenges of implementing EUM are magnified exponentially in an active conflict zone. The U.S. experience in providing security assistance to Ukraine has highlighted the immense difficulties of conducting on-the-ground monitoring in a hostile environment.

Security restrictions on the in-country travel of U.S. embassy personnel and the absence of a U.S. military presence to provide security for monitoring teams severely limit the ability to conduct in-person inspections, particularly for equipment located near combat zones.23 In these non-permissive environments, the U.S. is forced to rely heavily on “secondary EUM procedures,” which include remote methods and self-reporting from the Ukrainian government.23 While necessary under the circumstances, these methods inherently lack the same level of independent verification as a physical inspection by U.S. personnel. The DoD and DSCA are actively developing new policies and procedures for conducting EEUM in hostile environments, but these are still evolving and face the persistent challenges of access, security, and the fluid nature of the battlefield.11

VII. Conclusion#

The United States’ arms export control regime, governed by the Arms Export Control Act, is a complex and deliberately constructed system intended to serve the dual, and often conflicting, purposes of arming strategic partners and controlling the proliferation of advanced weaponry. The transfer of a major defense article like the F-16 fighter jet is not a simple commercial transaction but the entry point into a decades-long strategic relationship, bound by a web of legal obligations, technological dependencies, and intensive monitoring protocols. While the framework is robust on paper, its practical application reveals a system fraught with inherent tensions, systemic challenges, and a consistent pattern of political calculation that often prioritizes strategic relationships over strict legal enforcement.

The analysis presented in this blog reveals a fundamental and persistent tension at the heart of the U.S. arms transfer system. The AECA itself codifies a conflict between the foreign policy goal of strengthening allies and the national security goal of restraining the spread of arms. This tension is not a flaw in the system but its central, defining characteristic. It forces a continuous, case-by-case balancing act where the strategic value of a partnership is weighed against the risks of providing that partner with advanced military capabilities.

The case studies of Pakistan, Turkey, and Israel demonstrate that when these interests conflict, the preservation of the strategic relationship consistently takes precedence over the punitive enforcement of the AECA’s legal provisions. In each case, credible allegations of misuse or violations of transfer agreements were met not with the harsh penalties available under the law—such as sanctions or debarment—but with calibrated, often non-public responses designed to address the issue without rupturing the overarching partnership. The enforcement of the “ironclad agreement” is thus revealed to be highly malleable, a tool of statecraft applied with diplomatic nuance rather than as an inflexible legal mandate.

Furthermore, the system’s effectiveness is hampered by a critical design flaw in its accountability mechanism. The End-Use Monitoring program, the cornerstone of post-transfer verification, is operationally focused on confirming the physical custody and security of defense articles, not on monitoring their operational use. This “custody vs. use” dilemma creates a profound gap between the AECA’s legal requirement that weapons be used for legitimate purposes and the EUM program’s ability to verify compliance with that requirement. This gap, identified by the GAO and other independent analysts, means the current system is ill-equipped to address one of the most significant risks of arms transfers: their use in ways that violate international humanitarian law and harm civilians.

Finally, the entire oversight ecosystem is being progressively weakened by a deliberate policy of decreasing transparency. The shift toward aggregated public reporting, the opacity surrounding the vast Direct Commercial Sales market, and the increasing use of classification to shield information from public view are not inevitable outcomes of security needs but political choices. As demonstrated by the high level of transparency regarding aid to Ukraine, the executive branch possesses the capacity for greater openness. The choice to be less transparent elsewhere serves to insulate controversial arms transfer decisions from the public and congressional scrutiny that is essential for true accountability.

Disclaimer: The information provided is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. It is essential to seek the advice of a competent legal professional for your specific circumstances. Relying on this information without professional legal guidance is at your own risk.

Works cited#

Cover Image by Brigitte Werner from Pixabay, https://pixabay.com/photos/airplane-jet-fighter-f-16-659687/ ↩︎

Arms Export Control Act vs ITAR | Firearm Compliance - FastBound, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.fastbound.com/ffl-blog-arms-export-control-act-vs-itar-understanding-the-difference/ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

22 U.S. Code § 2778 - Control of arms exports and imports | U.S. …, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/22/2778 ↩︎

Arms Export Control Act (AECA), accessed July 26, 2025, https://deccspmddtc.servicenowservices.com/deccs?id=ddtc_kb_article_page&sys_id=b9a933addb7c930044f9ff621f961932 ↩︎ ↩︎

Arms Export Control Act - Wikipedia, accessed July 26, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arms_Export_Control_Act ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Fiscal Year 2024 U.S. Arms Transfers and Defense Trade - State Department, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.state.gov/fiscal-year-2024-u-s-arms-transfers-and-defense-trade ↩︎

Arms Export Control Act (AECA) - Security Assistance Management Manual, accessed July 26, 2025, https://samm.dsca.mil/glossary/arms-export-control-act-aeca ↩︎ ↩︎

Understand The ITAR - DDTC Public Portal - State Department, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.pmddtc.state.gov/?id=ddtc_public_portal_itar_landing ↩︎ ↩︎

Arms Export Control Act (AECA) - DDTC - State Department, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.pmddtc.state.gov/?id=ddtc_kb_article_page&sys_id=b9a933addb7c930044f9ff621f961932 ↩︎

Legal Basis for Arms Transfers - United States Department of State, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.state.gov/legal-basis-for-arms-transfers ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Chapter 8 - Security Assistance Management Manual, accessed July 26, 2025, https://samm.dsca.mil/chapter/chapter-8 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

End-Use Monitoring of Defense Articles and Services - DDTC, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.pmddtc.state.gov/sys_attachment.do?sys_id=5c52d53f1b01b8502b6ca932f54bcbd0 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Turkey (Türkiye): Possible U.S. Sale of F-16 Aircraft | Congress.gov, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R47493 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Chapter 4 | Defense Security Cooperation Agency, accessed July 26, 2025, https://samm.dsca.mil/chapter/chapter-4 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Transfer of Defense Articles: U.S. Sale and Export of U.S.-Made Arms to Foreign Entities, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/R46337 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

US Arms Exports Under Congressional Notification Thresholds - Forum on the Arms Trade, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.forumarmstrade.org/underthreshold.html ↩︎ ↩︎

Chapter - 5 Foreign Military SaleS ProceSS - Defense Security Cooperation University, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.dscu.edu/sites/default/files/2024-04/05-chapter.pdf ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

LOA StAndArd termS And COnditiOnS - Defense Security Cooperation University, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.dscu.edu/sites/default/files/2024-04/08-chapter.pdf ↩︎ ↩︎

I’ve read somewhere that a condition for a country to purchase something like a military fighter jet from the United States military is to not use it against the US military. What happens if this isn’t honored? - Quora, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.quora.com/Ive-read-somewhere-that-a-condition-for-a-country-to-purchase-something-like-a-military-fighter-jet-from-the-United-States-military-is-to-not-use-it-against-the-US-military-What-happens-if-this-isnt-honored ↩︎ ↩︎

FACT SHEET: Joint Resolutions of Disapproval under the Arms Export Control Act and Proposed Arms Sales to Israel - Senator Bernie Sanders, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.sanders.senate.gov/wp-content/uploads/FINAL_Fact-Sheet-Joint-Resolutions-of-Disapproval-for-Israel-arms-sales-003.pdf ↩︎ ↩︎

Arms Sales: Congressional Review Process - Congress.gov, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/RL31675 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Golden Sentry End-Use Monitoring Program | Defense Security …, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.dsca.mil/Programs/Golden-Sentry-End-Use-Monitoring ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

(U) Review of Department of State End- Use Monitoring in Ukraine - Office of Inspector General, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.stateoig.gov/uploads/report/report_pdf_file/isp-i-24-02-redacted.pdf ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

End-Use Monitoring of Defense Articles and Services - DDTC, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.pmddtc.state.gov/sys_attachment.do?sys_id=c9245d6e1b7ec914d1f1ea02f54bcb43 ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

End-Use Monitoring of Defense Articles and Defense Services, accessed July 26, 2025, https://deccspmddtc.servicenowservices.com/sys_attachment.do?sys_id=eebde4f1dbf51340528c750e0f961959 ↩︎

End-Use Monitoring of U.S.-Origin Defense Articles - State Department, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.state.gov/end-use-monitoring-of-u-s-origin-defense-articles ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

GAO-23-105856, NORTHERN TRIANGLE: DOD and State Need …, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-23-105856.pdf ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

18 End-UsE Monitoring and third- Party transfErs - Defense Security Cooperation University, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.dscu.edu/sites/default/files/2024-08/18-chapter.pdf ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

End-use monitoring is the key to success in foreign military sales | Article - Army.mil, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.army.mil/article/192447/end_use_monitoring_is_the_key_to_success_in_foreign_military_sales ↩︎

18 End-UsE Monitoring and third- Party transfErs - Defense Security Cooperation University, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.dscu.edu/sites/default/files/2024-04/18-chapter.pdf ↩︎ ↩︎

USA Reprimands Pakistan for Misusing F-16 Fighter Aircraft – CLAWS, accessed July 26, 2025, https://claws.co.in/usa-reprimands-pakistan-for-misusing-f-16-fighter-aircraft/ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

US warned Pakistan about misuse of F-16s after February dogfight …, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.theweek.in/news/world/2019/12/12/us-warned-pakistan-about-misuse-over-f-16s-after-february-dogfight-report.html ↩︎ ↩︎

Penalties & Oversight Agreements - DDTC - State Department, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.pmddtc.state.gov/ddtc_public/ddtc_public?id=ddtc_kb_article_page&sys_id=384b968adb3cd30044f9ff621f961941 ↩︎ ↩︎

Non-Compliance Penalties, accessed July 26, 2025, https://rci.ucmerced.edu/export-controls/export-violation-penalties ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

22 CFR Part 127 – Violations and Penalties - eCFR, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.ecfr.gov/current/title-22/chapter-I/subchapter-M/part-127 ↩︎

What agreements accompany sales of US combat aircraft? - Fly a jet fighter, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.flyajetfighter.com/what-agreements-accompany-sales-of-us-combat-aircraft/ ↩︎

Does the US have the ability to remotely “block” or “override” the F-16s it has exported - Reddit, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/CredibleDefense/comments/8eo61v/does_the_us_have_the_ability_to_remotely_block_or/ ↩︎

US looks into Pak’s use for F-16 jets against India - YouTube, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=609LPpJziR0 ↩︎

F-16 Misuse: Ambedkar Urges India to Act as Pakistan Violates US End-User Pact, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.deccanherald.com/india/pakistan-violates-end-use-agreement-by-using-f-16-against-india-ambedkar-urges-govt-to-take-it-up-with-us-3532546 ↩︎

US to look into violation of F-16 user-agreement by Pak - The Times of India, accessed July 26, 2025, https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/world/pakistan/us-to-look-into-violation-of-f-16-user-agreement-by-pak/articleshow/68239026.cms ↩︎

A/72/737–S/2018/96 General Assembly Security Council, accessed July 26, 2025, https://docs.un.org/en/A/72/737 ↩︎

US stipulated no overflights above Greek islands for F-16 sale to Turkey: report, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.turkishminute.com/2024/01/30/us-stipulated-no-overflight-above-greek-island-for-f-16-sale-turkey-report/ ↩︎

Israel/OPT: US-made munitions killed 43 civilians in two documented Israeli air strikes in Gaza – new investigation - Amnesty International, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2023/12/israel-opt-us-made-munitions-killed-43-civilians-in-two-documented-israeli-air-strikes-in-gaza-new-investigation/ ↩︎

No Weapons for War Crimes | Amnesty International USA, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.amnestyusa.org/blog/no-weapons-for-war-crimes/ ↩︎

GAO-20-176, SECURITY ASSISTANCE: Actions Needed to Assess …, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-20-176.pdf ↩︎ ↩︎

GAO-25-107077, HUMAN RIGHTS: State Can Improve Response to …, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-25-107077.pdf ↩︎ ↩︎

Expanding the Scope of End-Use Monitoring Policies to Address Operational Use of U.S.-Origin Weapons - RAND Corporation, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA2961-2.html ↩︎

Diminishing Transparency in the US Arms Trade - Stimson Center, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.stimson.org/2024/diminishing-transparency-in-the-us-arms-trade/ ↩︎ ↩︎

The Hidden Costs: Transparency and the US Arms Trade - Stimson Center, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.stimson.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/The-Hidden-Costs-Transparency-Paper-FINAL.pdf ↩︎

The Hidden Costs: Transparency and the US Arms Trade • Stimson …, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.stimson.org/2024/the-hidden-costs-transparency-and-the-us-arms-trade/ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Balancing Secrecy and Oversight: Navigating Familiar Barriers to U.S. Arms Trade Transparency - Stimson Center, accessed July 26, 2025, https://www.stimson.org/2024/balancing-secrecy-and-oversight-navigating-familiar-barriers-to-u-s-arms-trade-transparency/ ↩︎