Cambodia Employee Stock Options: A Strategic Guide

Table of Contents

This blog provides an exhaustive analysis of the legal, tax, and market landscape for employee stock options (ESOPs) in the Kingdom of Cambodia. It is designed to serve as a strategic guide for companies seeking to implement equity compensation schemes to attract, retain, and motivate talent in Cambodia’s rapidly evolving economy.1

The analysis reveals a regulatory environment characterized by significant ambiguity for private companies, contrasting with a more defined, albeit nascent, framework for entities listed on the Cambodia Securities Exchange (CSX). While there is no specific law governing private company ESOPs, the foundational Law on Commercial Enterprises (LCE) and general contract law provide the primary legal basis for their structure. This regulatory void places a paramount importance on meticulously drafted plan documents and flawless corporate governance.

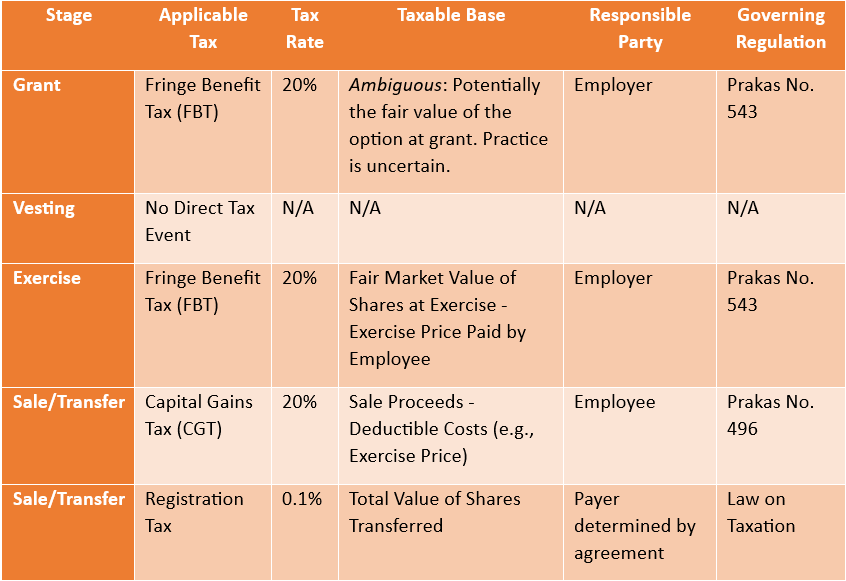

Taxation of equity compensation, however, is more definitive and presents considerable challenges. The introduction of Prakas No. 543 classifies stock options as a fringe benefit, subjecting the employer to a 20% Fringe Benefit Tax (FBT) on the value of the benefit conferred. Subsequently, upon the sale of shares, the employee is subject to a 20% Capital Gains Tax (CGT). The ambiguity surrounding the timing of the FBT event and the valuation of options for private companies represents the most significant compliance risk.

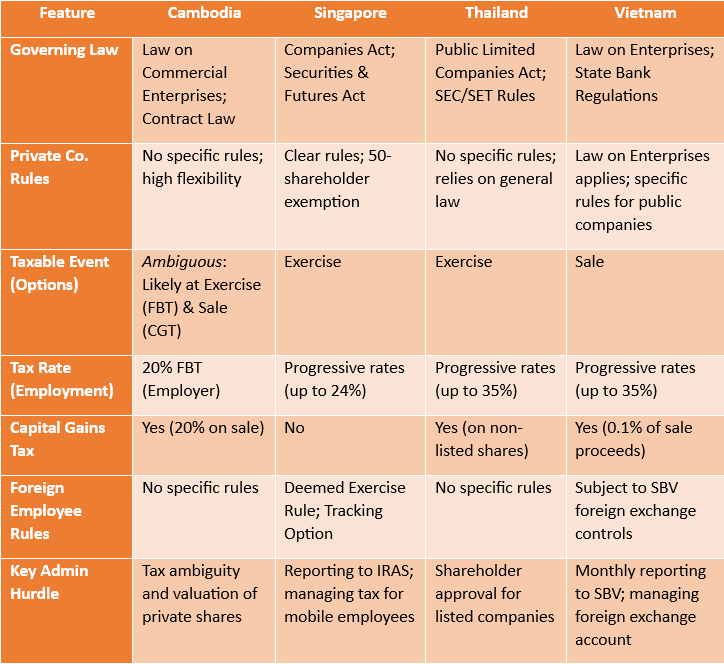

This blog dives deep into how ESOPs work in Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. We’re doing this to help figure things out for Cambodia, which has a bit more uncertainty. These ASEAN countries have some pretty different setups: Singapore’s system is super developed and easy to use, Thailand focuses a lot on the capital market, and Vietnam’s rules are all about control and foreign exchange. By picking out the best bits from these regional examples, we can put together a solid plan for setting up an ESOP in Cambodia that’s compliant, competitive, and actually works.

To wrap things up, the blog offers some smart tips for setting up ESOPs in Cambodia. It suggests going with regional norms, like a four-year vesting period with a one-year cliff. Plus, it really stresses the need to educate employees well, since financial literacy isn’t super high. It also recommends being super careful and organized with tax stuff, and thinking about a “cashless exercise” model to make it easier for people to get involved. Basically, by blending legal and tax insights with what works best in the region, this blog gives decision-makers the lowdown on how to really make ESOPs work as a strategic tool in Cambodia.

Equity Compensation in Cambodia’s Emerging Economy#

The Role of ESOPs in Attracting and Retaining Talent#

Cambodia’s economy is undergoing a dynamic transformation, with its technology sector emerging as a key driver of growth. This rapid development has ignited a competitive market for skilled professionals, leading to a projected shortage of over 600,000 IT professionals by 2025.2 In this talent-scarce environment, traditional compensation models are often insufficient for growth-stage companies and startups to compete with established corporations. ESOPs emerge as a critical strategic tool to bridge this gap.

For companies, particularly startups that must preserve cash for growth and other strategic needs, ESOPs provide an attractive, non-cash mechanism to offer competitive compensation packages.3 By granting employees the right to purchase company shares at a predetermined price in the future, companies can offer a significant potential financial upside that is directly tied to the long-term success of the enterprise. This approach is not only a necessity for resource-constrained startups but is also an established best practice for larger entities. The Cambodia Securities Exchange (CSX) explicitly encourages its listed companies to utilize ESOPs as a powerful incentive to increase employee morale, boost productivity, and secure the long-term commitment of high-quality human resources.4 This official endorsement underscores the recognized value of equity compensation within Cambodia’s formal economic framework.

In a market where specific skills are in high demand and short supply, a well-structured ESOP can be a decisive factor for a candidate choosing between a role at a startup and a more traditional corporate position. While the absence of specific ESOP regulations for private companies creates challenges, it also presents an opportunity. A company that proactively designs and implements a transparent, fair, and legally sound ESOP based on international best practices can distinguish itself as a sophisticated and forward-thinking employer. This can create a powerful “first-mover advantage” in the war for talent, establishing a reputation that attracts the most ambitious and capable professionals in the market. This is not merely a compensation tactic but a core component of a company’s human capital strategy.

Aligning Employee and Shareholder Interests for Long-Term Growth#

A fundamental strategic benefit of ESOPs is their ability to create a powerful alignment of interests between employees and shareholders. When employees become part-owners of the business, their perspective shifts from that of a wage-earner to that of a stakeholder. This fosters a culture of ownership, where individuals are intrinsically motivated to contribute to the company’s long-term value creation, as their personal financial success becomes directly linked to the company’s performance and valuation.3

This alignment drives tangible business outcomes. The improved labor-management relations and heightened morale can lead to enhanced productivity and innovation.4 Empirical evidence from other Asian markets supports this conclusion. Studies of ESOP implementation in Vietnam’s banking sector and among publicly traded firms in Japan have demonstrated a positive correlation with improved firm performance, including measurable gains in productivity and profitability.5 While these effects may manifest with a time lag, the long-term value proposition is clear. By giving employees “skin in the game,” companies can cultivate a more engaged, committed, and entrepreneurial workforce.

The broader adoption of ESOPs could also serve as a catalyst for the maturation of Cambodia’s entire startup ecosystem. As more employees are granted equity, their understanding of and engagement with concepts like valuation, funding rounds, and exit strategies will deepen. This creates a virtuous cycle: a more financially sophisticated talent pool is better equipped to contribute to high-growth ventures. Over time, employees who realize gains from successful exits may become the next generation of founders or angel investors, recycling both capital and invaluable experience back into the ecosystem, thereby accelerating its overall development.

Financial Literacy and Liquidity in the Cambodian Context#

Despite their strategic advantages, the successful implementation of ESOPs in Cambodia and the broader Southeast Asian region faces significant cultural and economic hurdles. A primary barrier is the relatively low level of financial literacy among the general workforce concerning complex instruments like stock options.6 Many employees may not fully grasp the mechanics of vesting, exercise, and potential dilution, leading them to undervalue the equity component of their compensation package. This is often compounded by a strong cultural and economic preference for immediate, tangible cash benefits over long-term, uncertain gains.6

The value proposition of an ESOP is fundamentally tied to the prospect of a future liquidity event, such as an Initial Public Offering (IPO) or a strategic acquisition, which allows employees to convert their shares into cash. In Cambodia’s nascent startup ecosystem, such exit events have been historically infrequent, and when they occur through private mergers and acquisitions, the valuations are often undisclosed.6 This uncertainty can make stock options seem like a lottery ticket rather than a reliable component of wealth creation, diminishing their motivational power for risk-averse employees.7

To overcome these challenges, companies must invest significantly in employee education. It is not enough to simply issue a grant letter. Effective implementation requires a proactive communication strategy, including company-wide learning sessions that clearly explain how ESOPs work, the potential risks and rewards, and the company’s long-term vision for growth and shareholder value.3 By demystifying the process and transparently managing expectations, companies can transform their ESOP from a misunderstood benefit into a powerful and appreciated tool for shared success.

Cambodian Employee Stock Options: Legal Landscape#

Structuring Share Capital and Corporate Authority#

The LCE serves as the foundational legal framework for all corporate entities in Cambodia and, in the absence of specific ESOP legislation, acts as the de facto rulebook for structuring equity compensation plans. Any ESOP must be designed in strict compliance with its provisions on corporate governance and share capital.

Under the LCE, a private limited company is required to have a minimum registered capital of KHR4,000,000 (approximately USD1,000) and must issue a minimum of 1,000 shares with a par value of at least KHR4,000 per share.8 Crucially, the LCE permits a company to create more than one class of shares, provided that the rights, privileges, restrictions, and conditions attached to each class are explicitly detailed in the company’s Memorandum and Articles of Association (M&A).8 This provision is the primary legal mechanism for creating a distinct class of shares for employees or for defining the terms of shares that will be reserved for an ESOP pool.

The issuance of any new shares, whether to investors or to employees upon the exercise of options, is a significant corporate act that requires formal approval. The company’s M&A must grant the authority to the Board of Directors or require a resolution from shareholders to create an option pool and to issue shares from that pool.9 Failure to obtain the proper corporate authorizations can render the share issuance invalid.

Furthermore, the LCE imposes a significant restriction on the transferability of shares. A shareholder may only transfer their shares to a third party with the endorsement of a majority of shareholders who represent at least three-quarters of the company’s total capital.10 This presents a major obstacle for employees who wish to sell their vested shares. To ensure the liquidity of employee shares post-exercise, this default rule must be explicitly modified or waived for ESOP-related shares, either within the M&A itself or through a comprehensive shareholders’ agreement. Without such a provision, the ESOP’s value is severely undermined, as employees would be unable to realize their gains.

Securities Law Implications: Private Placements vs. Public Offerings#

The Securities and Exchange Regulator of Cambodia (SERC) regulates the offering of securities in Cambodia. The regulatory requirements differ dramatically depending on whether the offering is classified as a private placement or a public offering.

An ESOP implemented by a private company for its employees would almost invariably fall under the definition of a private placement. An offering of securities is considered a private placement if it is made to a total of 30 persons or fewer and is not publicly advertised.11 Such offerings are subject to minimal regulatory oversight, requiring only that the issuing company file a report with the SERC upon completion of the placement.11 This light-touch approach provides private companies with considerable flexibility in designing and administering their internal ESOPs without undergoing a burdensome approval process.

In stark contrast, a public offering is a complex and highly regulated process intended for companies seeking to raise capital from the general public by listing on the CSX. This path is relevant for companies that wish to use ESOPs as a publicly traded entity, which enhances the liquidity and marketability of the employee shares.4 The process requires the company to appoint SERC-licensed underwriters, prepare extensive documentation, and undergo a formal Listing Eligibility Review (LER).4 The company must meet stringent quantitative criteria related to shareholders’ equity, net profit, and the number of minority shareholders, as well as non-quantitative requirements concerning corporate governance, such as board composition and the presence of independent directors.11

Absence of a Specific ESOP Framework for Private Companies#

A defining characteristic of the Cambodian legal environment is the complete absence of specific laws or regulations governing the design and implementation of ESOPs for private companies. Official guidance from the CSX acknowledges that for private companies, there are “no strict rules” regarding these matters.4 This regulatory void has profound practical consequences.

For one, it offers some flexibility. Companies are not bound by statutory requirements regarding key plan parameters such as vesting schedules, cliff periods, exercise periods, or the treatment of departing employees (“leavers”). These terms can be determined by the company and defined contractually.

On the other hand, this lack of a specific framework means that the entire legal enforceability of an ESOP rests upon the principles of general contract law and the corporate governance provisions of the LCE.8 The ESOP plan document, the grant agreement signed with each employee, and the associated corporate resolutions are not merely administrative paperwork; they constitute the entire legal foundation of the plan. Any ambiguity, internal inconsistency, or failure to adhere to the corporate procedures outlined in the LCE could expose the company to legal challenges and render the plan unenforceable. Therefore, while the environment is permissive, it demands an exceptionally high standard of legal drafting and procedural diligence. The most significant legal risk for a Cambodian ESOP is not the violation of a non-existent ESOP-specific rule, but a failure in fundamental corporate governance.

Integrating Equity Awards with Employment Contracts#

The Cambodian Labor Law, enacted in 1997, governs the relationship between employers and employees but is entirely silent on the subject of equity-based compensation.12 Its provisions are centered on traditional forms of remuneration, such as wages, bonuses, overtime, and other allowances.12 This silence necessitates careful structuring to ensure that an ESOP does not unintentionally create conflicts with statutory labor obligations.

A critical step is to legally characterize the ESOP as a discretionary, long-term incentive plan that is separate and distinct from an employee’s regular salary and wages. This is crucial to prevent the value of stock options from being included in the calculation base for statutory entitlements like overtime pay (which can be 150% to 200% of the regular wage) or severance payments.12 The employment contract and ESOP grant letter should explicitly state that the option grant is not part of the employee’s guaranteed remuneration.

The Labor Law also provides a rigid framework for employment contracts, primarily distinguishing between Fixed Duration Contracts (FDCs), which cannot exceed a total of two years, and Undetermined Duration Contracts (UDCs).12 The rules governing termination differ significantly for each contract type, with UDC employees afforded greater protections, including mandatory notice periods based on length of service and entitlement to seniority payments.12

This legal distinction has a direct and unavoidable impact on the design of an ESOP’s “leaver” provisions. The definitions of a “good leaver” (e.g., an employee who resigns after a certain period) and a “bad leaver” (e.g., an employee terminated for serious misconduct) within the ESOP must be meticulously aligned with the definitions, grounds, and procedures for termination as stipulated in the Labor Law. A company cannot simply create its own set of termination categories for the purpose of the ESOP that contradict the statutory framework. For example, if the plan states that an employee forfeits all vested options upon termination for “poor performance,” this must align with the legally valid grounds for termination of a UDC employee to be defensible against a potential legal challenge.

Cambodia’s Equity Compensation Tax Framework#

Valuation, Withholding Obligations, and Timing#

The most direct and significant tax implication for a company implementing an ESOP in Cambodia is the Fringe Benefit Tax (FBT). The legal basis for this tax is Prakas No. 543, issued by the Ministry of Economy and Finance, which explicitly expanded the definition of taxable fringe benefits to include the “provision of any part of company’s shares or stock options”.13

Under this regulation, the employer bears the full responsibility for withholding and remitting the FBT to the General Department of Taxation (GDT). The tax is levied at a flat rate of 20% on the total value of the fringe benefit provided to the employee.13 This creates a direct and potentially substantial cash liability for the company. If, for example, the taxable benefit conferred upon an employee through an option exercise is valued at USD100,000, the company is obligated to pay USD20,000 in cash to the GDT. This presents a significant cash flow challenge, particularly for startups, as it is a cash tax levied on a non-cash transaction. This dynamic could create a perverse incentive for a company to manage its valuation carefully or could even limit its ability to allow employees to exercise their options if the resulting FBT liability is too high.

The most critical area of uncertainty within the FBT framework is the ambiguity surrounding the timing of the taxable event and the methodology for valuation. Prakas No. 543 does not specify whether the “provision” of the benefit occurs at the date of grant, at each vesting date, or at the date of exercise.13 International best practice and the logical point of value realization strongly suggest that the taxable event should be the date of exercise. At this point, the “benefit” can be most clearly calculated as the difference between the fair market value (FMV) of the shares and the exercise price paid by the employee. However, the Prakas also fails to provide a prescribed method for determining the FMV of shares in a private, illiquid company. This lack of clear guidance requires companies to adopt a consistent, defensible, and well-documented valuation methodology, potentially supported by an independent valuator, to mitigate the risk of a future challenge from the GDT.4

The Tax Event at Liquidity#

While the FBT is an employer obligation, the Capital Gains Tax (CGT) is a tax levied on the employee at the point of liquidity. Under Prakas No. 496, a 20% CGT is imposed on the capital gains realized from the sale or transfer of capital assets, a category that explicitly includes shares of a company.14

The taxable event for CGT is unambiguous: it is triggered when the employee sells or otherwise transfers their shares.14 The tax is calculated on the net gain, which is defined as the sale proceeds less allowable deductible expenses. In the context of an ESOP, the primary deductible expense would be the exercise price the employee paid to acquire the shares.14 The employee is responsible for filing a tax return and paying the CGT due to the GDT within three months of realizing the gain.14

The combination of the 20% employer-paid FBT and the 20% employee-paid CGT results in a significant total tax leakage on the economic value created by the ESOP. Although these are not technically a “double tax” on the same party for the same event, the cumulative effect is that a substantial portion of the gain (the difference between the final sale price and the original exercise price) is captured by the state. This is a critical point that must be clearly and transparently communicated to employees to manage their expectations regarding the net, after-tax proceeds they can expect from their equity compensation.

Registration Tax on Share Transfers#

Apart from FBT and CGT, a transactional tax known as the Registration Tax applies to the transfer of shares. The Law on Taxation stipulates a tax rate of 0.1% of the total value of the shares being transferred.10 This tax is levied at the time the transfer is officially recorded. While the rate is nominal compared to FBT and CGT, it is an additional compliance step and cost that must be factored into the process of an employee selling their shares. The parties typically determine the responsibility for payment to the transaction but should be clearly addressed in any share purchase agreement.

Tax Planning and Optimization Strategies#

Given the legal ambiguities and the significant tax burden, careful planning is essential.

FBT Timing and Valuation: Companies must formally adopt a clear and consistent policy on the timing and valuation for FBT purposes. Taxing the benefit at the point of exercise is the most common and defensible international standard. The valuation of private company shares should be based on a recognized methodology (e.g., discounted cash flow, comparable company analysis) and be well-documented to withstand potential scrutiny.

Exercise Price Strategy: The exercise price set at the time of grant directly impacts the future FBT liability. Setting a higher exercise price, closer to the FMV at grant, reduces the taxable “benefit” at exercise, thereby lowering the company’s future FBT cash outflow. However, this makes the option less attractive to the employee. Conversely, a nominal exercise price maximizes the potential gain for the employee but also maximizes the FBT liability for the company. This trade-off must be carefully balanced.

Employee Communication: A comprehensive communication plan is vital. Employees must be educated on the full tax lifecycle of their options, including the company’s FBT obligation at exercise and their personal CGT and Registration Tax obligations at sale. Providing hypothetical examples can help illustrate the net financial outcome and prevent future misunderstandings.

ESOP Frameworks in Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam#

Since Cambodia doesn’t have specific regulations for ESOPs yet, it’s a good idea to look at what other ASEAN countries like Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam are doing. They all have different ways of handling ESOPs, and we can learn a lot from their approaches to help us set up a good plan here in Cambodia.

Singapore: The Gold Standard#

Singapore’s framework is widely regarded as the regional benchmark for clarity, sophistication, and comprehensiveness. It is a facilitative system designed to empower companies with clear rules while ensuring robust corporate governance and tax compliance.

Legal Framework: The system is built upon a clear interplay of several key statutes. The Companies Act provides the corporate governance foundation, including a crucial exemption that allows private companies to exceed the 50-shareholder limit for the purpose of an ESOP, thereby preventing an inadvertent conversion to a public company.15 For publicly listed companies, the Singapore Exchange (SGX) Listing Rules prescribe detailed requirements on plan size, participant eligibility, and pricing discounts.16

Tax Treatment: Singapore’s tax treatment is a model of clarity. The taxable event is definitively the point of exercise for stock options and the point of vesting for Restricted Stock Units (RSUs).15 The gain, calculated as the difference between the market value and the price paid by the employee, is taxed as regular employment income at progressive rates.17 Critically, Singapore does not levy a capital gains tax, meaning any subsequent appreciation in the share value upon sale is tax-free for the employee.18

Foreign Employees: The framework includes sophisticated provisions for a mobile workforce. The “Deemed Exercise Rule” requires non-citizen employees to pay tax on unexercised options upon cessation of employment or departure from Singapore, preventing tax avoidance.15 As an alternative, employers can apply for the “Tracking Option,” which allows them to track the employee post-departure and report the taxable gain only when the option is actually exercised, offering greater flexibility.15

Thailand: The Public Market Model#

Thailand’s regulatory approach is primarily capital-market-centric, with a strong focus on rules for companies listed on the Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET). Like Cambodia, the framework for private companies is less developed and relies on general corporate law.

Legal Framework: The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) of Thailand has established clear rules for two distinct types of employee equity plans for listed companies. The traditional ESOP involves the issuance of new shares or warrants to employees, which can have a dilutive effect on existing shareholders.19 In contrast, the Employee Joint Investment Plan (EJIP) is a non-dilutive alternative where the company contributes funds to help employees purchase existing company shares from the open market.19 Both types of plans for listed companies require shareholder approval.19

Tax Treatment: The tax treatment is straightforward and aligns with international norms. The taxable event occurs at the exercise of the option. The benefit, calculated as the difference between the market price at exercise and the employee’s exercise price, is considered assessable income and is subject to Thailand’s progressive personal income tax rates.19

Key Lesson: The existence of the EJIP model provides a valuable strategic lesson. It directly addresses a primary concern of existing investors—shareholder dilution. For a Cambodian company with a concentrated ownership structure, adopting an EJIP-style, non-dilutive plan could be a more palatable way to introduce employee equity ownership.

Vietnam: Foreign Exchange Control#

Vietnam’s ESOP framework is unique in the region, as it is fundamentally shaped by the state’s desire to control foreign currency flows. This makes it a control-oriented system, where the rules are driven by the State Bank of Vietnam (SBV) rather than corporate or securities law.

Legal Framework: Historically, any plan offered by a foreign parent company to Vietnamese employees was considered an “offshore indirect investment” and required a burdensome registration and approval process with the SBV.20

Recent Reforms (Circular 23/2024): A significant recent reform, effective August 2024, has abolished the SBV registration requirement, drastically reducing the administrative burden.21 However, this liberalization comes with a critical trade-off: the new circular explicitly prohibits any ESOP structure that requires Vietnamese employees to remit funds abroad to purchase shares.21 This effectively limits plans to two forms: the direct award of free shares or plans with a “cashless exercise” mechanism where no funds leave Vietnam.

Tax Treatment: Vietnam’s tax system for ESOPs is complex. The taxable event is deferred until the point of sale of the shares. At that time, the gain is bifurcated and subject to two different taxes: a portion is treated as employment income and taxed at progressive rates up to 35%, while the remainder is treated as income from securities transfer and taxed at a nominal rate of 0.1% on the total sale proceeds.22

A Synthesis of Key Differences#

The regulatory approaches of these three nations represent three distinct archetypes. Singapore’s is facilitative, Thailand’s is capital-market-centric, and Vietnam’s is control-oriented. Cambodia’s current laissez-faire approach for private companies is a product of inaction rather than design. Given its generally open investment climate and the focus of its securities regulators on developing the CSX, Cambodia is more likely to evolve towards a Thai-style model, with an initial focus on rules for listed companies, rather than a Vietnamese-style control model.23

Furthermore, Vietnam’s forced adoption of cashless structures due to currency controls provides a compelling best-practice model for Cambodia. Given the low financial literacy and potential lack of liquid capital among employees in the region,9 designing a Cambodian ESOP around a “cashless exercise” (where a portion of shares is automatically sold to cover the exercise price and taxes) or a phantom stock/Stock Appreciation Right (SAR) plan is a strategically sound approach. It removes a significant barrier to participation and makes the benefit more accessible and valuable to the employee base.

A Blueprint for Best Practices#

Given the absence of a specific legal framework for private company ESOPs in Cambodia, the plan’s design and documentation are paramount. A robust and enforceable plan can be constructed by adhering to the foundational principles of the LCE and incorporating best practices observed in more mature regional markets.

Option Pool Sizing, Vesting Schedules, Cliff Periods, and Exercise Price#

Option Pool Sizing: The option pool is the total number of shares reserved for issuing employees. In Southeast Asia, it is common for seed-stage startups to allocate 10% or less of their total equity to the ESOP pool.24 A critical best practice is for this pool to be periodically “topped up” or expanded in subsequent fundraising rounds to ensure the company has enough equity to continue attracting new talent as it grows.25 The creation and any subsequent increase of the option pool must be formally approved by the company’s shareholders as it results in the dilution of their ownership.26

Vesting Schedules and Cliff Periods: Vesting is the process by which an employee earns the right to their options over time. The regional and global standard is a four-year vesting schedule with a one-year cliff.25 Under this model, an employee earns no options for the first year of service (the “cliff”). Upon completing one year, 25% of their total options vest immediately. The remaining 75% then vest in equal installments over the next three years, often on a monthly or quarterly basis.27 This structure is designed to incentivize long-term commitment and retain employees beyond the initial year.

Exercise Price (Strike Price): The exercise price is the fixed price per share that an employee must pay to purchase the shares upon exercising their vested options. This price is set at the date the options are granted. Companies have flexibility in setting this price. It can be set at the fair market value (FMV) of the shares at the time of grant, which is common practice to align with investor pricing. Alternatively, to make the options more attractive, companies can set the price at a discount to FMV or at a nominal par value.25 As discussed in the taxation section, this decision has a direct impact on the company’s future FBT liability.

The ESOP Agreement, Grant Letters, and Board Resolutions#

The legal integrity of the ESOP hinges on a set of clear, comprehensive, and internally consistent documents.

The ESOP Agreement (Plan Document): This is the master document that governs the entire plan. It should be formally adopted by a Board of Directors resolution and approved by shareholders. It must detail all aspects of the plan, including the total size of the option pool, eligibility criteria for participants, the vesting schedule, the process for exercising options, and the treatment of leavers.

The Grant Letter (Award Agreement): This is the individual contract between the company and each employee participant. It specifies the number of options granted, the exercise price, the specific grant date, and the vesting commencement date. It should explicitly reference the master ESOP Agreement and require the employee to acknowledge and agree to its terms.

Board and Shareholder Resolutions: Every significant action related to the ESOP must be supported by formal corporate resolutions, as required by the LCE. This includes the initial adoption of the plan, the creation of the option pool (which may require amending the M&A), the approval of each individual grant of options, and the authorization to issue new shares upon exercise.9 Meticulous record-keeping of these resolutions is essential to prove the plan’s legal validity.

Roles of the Board, Plan Administrator, and Communication Strategies#

Plan Administration: The ESOP Agreement should designate a plan administrator, which is typically the company’s Board of Directors or a dedicated compensation committee of the board. The administrator is responsible for interpreting the plan’s terms, approving grants, and making decisions on any discretionary matters.

Communication: As highlighted previously, clear and continuous communication is vital for the success of an ESOP in a market with low financial literacy. The company should conduct initial onboarding sessions to explain the plan to new participants and provide regular updates on their vesting progress.3 It is a best practice for founders or senior leaders to lead these discussions to convey the strategic importance of the plan and build employee buy-in.25

Management Tools: While a small startup may initially manage its ESOP on a spreadsheet, as the company grows and the number of participants increases, it becomes crucial to adopt specialized software or tools to accurately track grants, vesting schedules, and exercises. This ensures administrative accuracy and helps in preparing for due diligence in future funding rounds or an exit event.25

Leaver & Change of Control Scenarios#

The ESOP agreement must clearly define what happens to an employee’s options when they leave the company. These provisions are critical for protecting the company’s equity and ensuring fairness.

Good Leavers vs. Bad Leavers: Plans typically distinguish between “good leavers” (e.g., resignation, retirement, redundancy) and “bad leavers” (e.g., termination for serious misconduct, breach of contract).15 A good leaver is generally allowed to exercise their vested options within a specified timeframe after their departure (the Post-Termination Exercise Period or PTEP), while a bad leaver may forfeit all options, including those that have already vested. As noted, these definitions must be carefully aligned with the Cambodian Labor Law.

Post-Termination Exercise Period (PTEP): This is the window of time a departing employee has to exercise their vested options. Historically, a 90-day PTEP was common, but there is a growing trend, particularly in competitive tech markets, to offer longer periods (e.g., 12 months or more) to give employees more financial flexibility.25 A short PTEP can force employees to make a difficult decision to purchase shares without a clear path to liquidity, diminishing the value of the benefit.

Change of Control (Accelerated Vesting): Many plans include a “change of control” clause that provides for accelerated vesting in the event of a merger or acquisition. This means that some or all of an employee’s unvested options will automatically vest upon closing. This is a key provision that protects employees and allows them to participate in the financial upside of an exit event they helped to create.24

Market Practices and Case Studies#

Analysis of ESOP Adoption Trends in Southeast Asia’s Tech Sector#

The use of ESOPs as a strategic compensation tool is a rapidly growing trend across Southeast Asia’s vibrant technology and startup landscape. The practice is evolving from a niche benefit for senior management to a broad-based tool for fostering an ownership culture across all levels of an organization.

A 2024 study on the state of ESOPs in the region revealed a significant increase in adoption. While in 2021, six out of ten startups offered ESOPs, that figure has now risen to eight out of ten.28 This indicates a clear recognition among founders of the strategic value of equity compensation in a competitive talent market. The trend is also towards earlier implementation, with many companies now establishing ESOPs at the seed stage or even earlier, and broader participation, with seven out of ten companies offering stock options to employees outside of the senior management team.25 This shift reflects a deeper understanding that aligning incentives across the entire organization can drive collective success.24

However, challenges remain. Many founders still lack a deep understanding of how to structure and manage ESOPs effectively, particularly regarding post-termination exercise periods and providing liquidity for employees prior to a major exit event.24 A concerning finding was that a significant number of companies had punitive clauses that dissolved all options, including vested ones, upon an employee’s departure, effectively creating “golden handcuffs” rather than a true ownership incentive.24

Illustrative Case Studies of Publicly Disclosed Plans#

The most visible examples of ESOP implementation in Southeast Asia come from the region’s publicly listed tech giants, whose success stories have popularized the concept of startup equity creating significant wealth for early employees.

Grab Holdings Ltd. (NASDAQ: GRAB): As a “super app” giant headquartered in Singapore, Grab has been a prominent user of equity compensation to attract and retain talent across its diverse operations in mobility, delivery, and financial services.29 The company’s successful public listing provided a major liquidity event for its employees, demonstrating the potential upside of startup stock options and setting a powerful precedent for the entire region.29

Sea Limited (NYSE: SE): Another Singapore-based conglomerate with major interests in e-commerce (Shopee) and digital entertainment (Garena), Sea Ltd. has also relied heavily on equity awards to fuel its rapid expansion.29 The performance of its stock on the New York Stock Exchange has served as a clear benchmark for how employee equity can translate into substantial financial gains, reinforcing the value proposition of ESOPs for aspiring tech professionals in Southeast Asia.29

These high-profile cases, along with others in the Philippines like Grab and SAP58, have been instrumental in raising awareness and creating demand for ESOPs among the region’s talent pool. They provide a tangible blueprint for how early-stage risk-taking can be rewarded and serve as motivational examples for employees in Cambodia’s own burgeoning tech scene.

Hypothetical Structuring for a Cambodian Tech Startup#

To illustrate the practical application of the principles discussed in this blog, consider the case of “KhmerDev,” a hypothetical seed-stage software development startup in Phnom Penh.

Corporate and Legal Structure: KhmerDev is incorporated as a private limited company under the LCE. At its seed funding round, the founders and investors agree to amend the M&A to authorize a share option pool representing 10% of the fully diluted share capital. The Board of Directors is appointed plan administrator.

Plan Design:

Eligibility: All full-time employees are eligible.

Vesting: Options are subject to a four-year vesting schedule with a one-year cliff. 25% of options vest on the first anniversary of the employee’s start date, with the remainder vesting monthly over the subsequent 36 months.

Exercise Price: The exercise price for the initial grants is set at the par value of the shares (KHR4,000) to maximize the potential upside for early employees.

Leaver Provisions: The plan distinguishes between a Good Leaver (resignation after the cliff, redundancy) and a Bad Leaver (termination for serious misconduct as defined by the Labor Law). Good Leavers have a 12-month PTEP to exercise their vested options. Bad Leavers forfeit all options, vested and unvested.

Liquidity: The plan includes a “cashless exercise” provision, allowing employees to exercise their options without an upfront cash payment. It also features a single-trigger acceleration clause, where 100% of unvested options vest immediately upon a Change of Control.

Tax Compliance: KhmerDev’s management, in consultation with their tax advisor, adopts a formal policy to treat the exercise of options as the taxable event for FBT purposes. They engage an independent valuation firm annually to determine the FMV of the company’s shares. When an employee exercises their options, KhmerDev calculates the benefit (FMV minus exercise price), withholds the 20% FBT, and remits it to the GDT.

Employee Communication: Upon hiring, every new employee receives a clear grant letter and a simplified plan summary. The CEO conducts quarterly all-hands meetings where the company’s progress is discussed, and the value and mechanics of the ESOP are reinforced to ensure employees understand and appreciate their stake in the company’s future.

By adopting this structure, KhmerDev can offer a competitive, transparent, and legally defensible ESOP that aligns with regional best practices while navigating the specific constraints of the Cambodian legal and tax environment.

Strategic Recommendations and Future Outlook#

Implementing a Compliant and Effective ESOP in Cambodia#

For any company considering the implementation of an ESOP in Cambodia, a strategic approach grounded in legal diligence, tax prudence, and clear communication is essential. The following recommendations synthesize the analysis of this blog into an actionable framework.

Prioritize Corporate Governance: In the absence of specific ESOP laws, the LCE is the ultimate authority. Ensure every step—from amending the M&A to create an option pool, to board resolutions for grants, to the issuance of shares upon exercise—is meticulously documented and compliant with Cambodian corporate law. This is the bedrock of a legally defensible plan.

Adopt Regional Best Practices for Plan Design: Do not design in a vacuum. Adopt the prevailing regional standard of a four-year vesting schedule with a one-year cliff. Offer a generous Post-Termination Exercise Period (PTEP) of at least 12 months to provide real value to departing employees. Include a Change of Control clause with accelerated vesting to protect and reward employees in an exit scenario.

Implement a “Cashless Exercise” Mechanism: To overcome the dual challenges of low employee liquidity and regional financial literacy, structure the plan to enable a cashless exercise. This removes a significant barrier to participation and makes the benefit more accessible and valuable to the entire workforce.

Develop a Proactive Tax Compliance Strategy:

Formally adopt a policy to recognize the exercise of an option as the taxable event for the 20% employer-paid FBT.

Establish a consistent and defensible methodology for valuing private company stocks, supported by periodic independent appraisals. This is the most critical step in mitigating tax risk.

Budget FBT as a future cash liability. The company must have the financial capacity to pay this tax when employees exercise their options.

Invest Heavily in Employee Education: The success of an ESOP is contingent on it being understood and valued. Implement a comprehensive communication strategy that includes simple, clear documentation in both English and Khmer, onboarding sessions for new hires, and regular company-wide updates that link company performance to potential equity value.

Mitigating Legal & Tax Risks#

The primary risks in Cambodia stem from ambiguity. Mitigation, therefore, relies on creating certainty through process and documentation.

Legal Risk Mitigation: The greatest legal risk is an internal challenge from a disgruntled employee or shareholder claiming the plan is invalid. This is mitigated by ensuring flawless corporate governance and creating an ESOP Agreement and Grant Letter that are clear, comprehensive, and based on sound contract law principles. The plan’s terms, particularly leaver provisions, must be carefully harmonized with the requirements of the Cambodian Labor Law.

Tax Risk Mitigation: The greatest tax risk is a challenge from the GDT on the timing or valuation of the FBT calculation. This is mitigated by adopting a conservative position (taxing at exercise), using a robust and independent valuation methodology, and maintaining meticulous records of all calculations and payments. Seeking a formal ruling from the GDT, while potentially time-consuming, could provide the ultimate certainty.

Anticipating Regulatory Developments#

The Cambodian regulatory landscape for equity compensation is likely to evolve as the economy matures and the capital markets develop. Companies implementing ESOPs today should anticipate future changes.

It is probable that the SERC and CSX will be the first to issue more detailed regulations, likely focusing on ESOPs for public or soon-to-be-public companies, mirroring the development path seen in Thailand. This could include plan size rules, shareholder approval and disclosure requirements.

As the tech ecosystem grows and ESOPs become more common, the Ministry of Economy and Finance and the GDT may issue further guidance to clarify the ambiguities in the current tax framework, particularly concerning the FBT taxable event and valuation methods for private companies.

Finally, while less likely in the short term, the Ministry of Labour and Vocational Training may eventually address equity-based awards in future amendments to the Labor Law. Companies that build their plans on a foundation of fairness, transparency, and international best practices will be best positioned to adapt to any future regulatory developments. By establishing a high standard now, they not only gain a competitive advantage but also contribute to shaping a positive and sustainable future for equity compensation in the Kingdom of Cambodia.

Disclaimer: The information provided is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. It is essential to seek the advice of a competent legal professional for your specific circumstances. Relying on this information without professional legal guidance is at your own risk.

Works cited#

Cover image from Pixabay, https://pixabay.com/photos/stock-trading-monitor-business-1863880/ ↩︎

Inside Cambodia’s Thriving Tech Hub: Startups and Success Stories, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.nucamp.co/blog/coding-bootcamp-cambodia-khm-inside-cambodias-thriving-tech-hub-startups-and-success-stories ↩︎

A guide to employee stock options for startups in emerging markets - Accion, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.accion.org/a-guide-to-employee-stock-options-for-startups-in-emerging-markets/ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Topic 1 - Listing Guide, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.acledasecurities.com.kh/as/assets/pdf_zip/My%20Learnings-Others-Topic%201-Listing%20Guide.pdf ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Does Employee Stock Ownership Work? Evidence from publicly-traded firms in Japan, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.rieti.go.jp/jp/publications/dp/16e073.pdf ↩︎

Stock options plan doesn’t work in Southeast Asia | by Benny Tjia | Medium, accessed October 2, 2025, https://medium.com/@bennytjia/startup-stock-options-plan-what-it-is-and-why-it-doesnt-work-in-southeast-asia-c2e8e05a47dd ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

What’s the point of employee stock options in start ups : r/FPandA - Reddit, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.reddit.com/r/FPandA/comments/1d14n6j/whats_the_point_of_employee_stock_options_in/ ↩︎

LEGAL FRAMEWORK FOR DOING BUSINESS 1. Establishment of Business Entities The Law on Commercial Enterprises (LCE), which was prom - Ministry of Foreign Affairs and International Cooperation, accessed October 2, 2025, https://mfaic.gov.kh/files/uploads/PDFDoingBussinessForCambodia/2_Legal_Framework_for_Doing_B.pdf ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Corporate Compliance Requirements for Cambodia Companies, accessed October 2, 2025, https://cambodia.acclime.com/guides/corporate-compliance-requirements/ ↩︎ ↩︎

Doing Business in Cambodia: Overview | Practical Law - Thomson Reuters, accessed October 2, 2025, https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/3-524-4317?transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default) ↩︎ ↩︎

Cambodia Capital Market Guide - HBS LAW, accessed October 2, 2025, https://hbslaw.asia/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/Capital-Market-Guide-2020.pdf ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Navigating Cambodia’s Labour Laws: A Guide for Employers | B2B, accessed October 2, 2025, https://b2b-cambodia.com/business/guides/overviews/navigating-cambodias-labour-laws-a-guide-for-employers/ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Tax on Salary - Technical Update - KPMG International, accessed October 2, 2025, https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/kh/pdf/technical-update/2021/TU-%20Prakas%20543_Tax%20on%20Salary_121021%20(003)%20new%20version%201.pdf ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Cambodia MEF Issues Prakas to Impose Capital Gains Tax on Resident and Non-Resident Taxpayers | Rajah & Tann Asia, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.rajahtannasia.com/viewpoints/cambodia-mef-issues-prakas-to-impose-capital-gains-tax-on-resident-and-non-resident-taxpayers/ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Setting up an equity compensation plan – Legal and Tax …, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.grantthornton.sg/insights/2025-insights/setting-up-an-equity-compensation-plan–legal-and-tax-considerations/ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Employee Share Plans in Singapore: Regulatory Overview - WongPartnership, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.wongpartnership.com/upload/medias/KnowledgeInsight/document/17650/EmployeeSharePlansinSingaporeRegulatoryOverview.pdf ↩︎

Navigating ESOP Taxation in Singapore: A Guide for Businesses | Eqvista, accessed October 2, 2025, https://eqvista.com/esop/esop-taxation-in-singapore/ ↩︎

Taxation on Employee Stock Ownership Plans (ESOPs) in Southeast Asia - Carta, accessed October 2, 2025, https://carta.com/learn/startups/equity-management/taxation-esops-southeast-asia/ ↩︎

ESOP - The Stock Exchange of Thailand, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.set.or.th/en/listing/listed-company/financial-instruments/esop ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

How a Vietnamese employee participates in an offshore ESOP properly and tax implications? - VDB Loi, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.vdb-loi.com/vn_publications/how-a-vietnamese-employee-participates-in-an-offshore-esop-properly-and-tax-implications/ ↩︎

Update on ESOP of Foreign Organization in Vietnam - KPMG International, accessed October 2, 2025, https://kpmg.com/vn/en/home/insights/2024/08/update-on-esop.html ↩︎ ↩︎

Employee Stock Ownership Plans Compared: Vietnam And Australia. - Conventus Law, accessed October 2, 2025, https://conventuslaw.com/report/employee-stock-ownership-plans-compared-vietnam-and-australia/ ↩︎

2022 Investment Climate Statements: Cambodia - State Department, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.state.gov/reports/2022-investment-climate-statements/cambodia ↩︎

State of ESOPs in Southeast Asia - Webflow, accessed October 2, 2025, https://uploads-ssl.webflow.com/608669ac5e699160be2e44ad/61b326a7d4e466686ad32c6e_State%20of%20ESOPs%20in%20SEA.pdf ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Saison Capital – The State of ESOPs in ASIA 2024 Findings, accessed October 2, 2025, https://hkifoa.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/state-of-esops-in-asia-saison-capital.pdf ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

ESOP of non-public companies in Vietnam - Asia Legal, accessed October 2, 2025, https://asialegal.vn/esop-of-normal-joint-stock-company/ ↩︎

Unlocking the potential of ESOP - Wamda, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.wamda.com/en/2023/06/unlocking-potential-esop ↩︎

Latest trend in SEA startups? It’s ESOP - Tech in Asia, accessed October 2, 2025, https://www.techinasia.com/latest-trend-sea-startups-esop ↩︎

Recent Success of Southeast Asian Companies Listed in the U.S. - ARC Group, accessed October 2, 2025, https://arc-group.com/southeast-asian-companies-listed-us/ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎