A Practical Guide to the Cambodian Energy Market for Professionals

Table of Contents

The energy sector of the Kingdom of Cambodia has undergone a metamorphosis over the last two decades, evolving from a fragmented, diesel-dependent system into a unified national grid powered predominantly by hydropower and coal, with a rapidly accelerating pivot toward solar energy. For legal practitioners, investment advisors, and energy consultants, Cambodia presents a unique paradox: it is a highly regulated, single-buyer market that offers some of the most robust, bankable Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) in Southeast Asia, yet it remains cautious regarding full market liberalization.1

As of the end of 2024, the sector operates under a consolidated framework where the state-owned utility, Electricité du Cambodge (EDC), serves as the central nervous system—acting as the grid operator, the sole off-taker, and the primary distributor in urban centers. The total installed capacity has reached approximately 5,044 megawatts (MW), supporting a national grid that now connects nearly 99.99% of consumers and 14,048 villages.2 This represents a monumental shift from the early 2000s when electricity access was a luxury reserved for urban elites.

However, the market is currently navigating a complex transition. The Power Development Master Plan 2022-2040 signals a decisive move away from fossil fuels, instituting a moratorium on new coal plants and setting ambitious targets for variable renewable energy (VRE). This shift has necessitated a complete overhaul of the regulatory framework governing rooftop solar and distributed generation, culminating in the issuance of new Prakas and Regulations in late 2024 and 2025. These instruments introduce quotas, compensation tariffs, and technical classifications that fundamentally alter the return on investment (ROI) calculations for Commercial and Industrial (C&I) consumers.

This blog is a straightforward guide to Cambodia’s energy market, perfect for professionals diving into the scene. Think of it as your essential reference for legal and financial pros getting started here. We’re going to break down the key laws, how the Electricity Authority of Cambodia (EAC) manages licenses, what’s really happening with generation and transmission, and the specific contract risks you’ll find in Cambodian PPAs. Plus, we’ll put Cambodia’s regulations into perspective by comparing them with Vietnam’s emerging wholesale markets, Thailand’s “Enhanced Single Buyer” setup, and the more open pools in the US and EU.

The Legal and Regulatory Architecture#

The governance of Cambodia’s power sector is characterized by a deliberate bifurcation of powers between policy formulation and regulatory oversight. This separation, codified in the primary legislation, is essential for investors to understand, as it dictates the approval pathways for projects.

The Electricity Law of the Kingdom of Cambodia#

The foundational legal instrument governing the sector is the Electricity Law of the Kingdom of Cambodia, promulgated by Royal Decree No. NS/RKM/0201/03 on February 2, 2001. The law has been amended twice, in 2007 and 2015, to refine the regulatory scope and adapt to the sector’s growth.2

The Electricity Law establishes the fundamental principles for operations in the electric power industry. Its primary objective is to establish a framework for the supply and use of electricity that ensures efficiency, quality, sustainability, and transparency.2 For legal practitioners, the key takeaways from the Law are the definitions of rights and obligations for service providers and consumers, and the establishment of the regulator.

A critical aspect of the 2015 amendment was the clarification of Article 3, which explicitly separates the roles of the government and the regulator. This legislative move was designed to minimize political interference in technical regulation and tariff setting, thereby enhancing investor confidence.2

Institutional Roles and Responsibilities#

The Cambodian power sector is governed by two primary entities: the Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME) and the Electricity Authority of Cambodia (EAC). Understanding the demarcation between these two is critical for project development.

Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME): The Policy Architect#

The MME acts as the executive arm of the government in the energy sector. It is responsible for setting and administering government policies, strategies, and long-term planning.2

For investors looking to develop large-scale Independent Power Projects (IPPs), the MME is the primary counterparty for the Implementation Agreement (IA). The IA provides sovereign guarantees and outlines the government’s support for the project.

Key Mandates of the MME:

Strategic Planning: The MME formulates the Power Development Plan (PDP), a master document that dictates the energy mix, generation targets, and transmission roadmap for the next two decades. Decisions on whether to prioritize hydro over coal or solar over gas originate here.

Policy Decisions: The MME holds the authority to decide on investments in the rehabilitation and development of the power sector, restructuring of public utilities, and the promotion of indigenous energy resources.2

Import/Export: Decisions regarding cross-border energy trade (e.g., importing power from Laos or Vietnam) and regional grid integration fall under the MME’s jurisdiction.

Technical Standards: The MME issues the technical standards related to operation, safety, and environment. While the EAC enforces these standards, the MME defines them.2

Electricity Authority of Cambodia (EAC): The Independent Regulator#

The EAC operates as an autonomous public legal entity. It is not a ministry but a regulatory agency with a mandate to govern the relationship between the delivery, receiving, and use of electricity.2

For operational entities, the EAC is the day-to-day regulator. No entity can generate, transmit, distribute, or sell electricity in Cambodia without a license issued by the EAC.

Key Regulatory Functions of the EAC:

Licensing Authority: The EAC has the sole power to issue, revise, suspend, revoke, or deny licenses. This includes generation licenses for IPPs, distribution licenses for Rural Electricity Enterprises (REEs), and the new category of licenses for rooftop solar service providers.2

Tariff Determination: The EAC approves tariff rates and charges. Unlike deregulated markets where prices are discovered via spot auctions, Cambodian tariffs are calculated based on the “Reasonable Cost” principle, ensuring that licensees can recover costs and earn a fair return while protecting consumers.2

Dispute Resolution: The EAC acts as a quasi-judicial body to resolve disputes. If a consumer disputes a bill or an IPP disputes a curtailment order, the complaint is first filed with the EAC. The Law empowers the EAC to mediate and, if necessary, issue binding judgments.2

Enforcement and Penalties: The EAC monitors compliance with the Grid Code and license conditions. It has the authority to impose monetary penalties or disconnect supply for violations.2

Electricité du Cambodge (EDC): The State Utility#

While not a regulator, EDC is the dominant market participant. It is a state-owned limited liability company that holds a Consolidated License (License No. 001L) granting it the right to generate, transmit, and distribute power nationwide.2

EDC acts as the “Single Buyer” in the market. It purchases power from IPPs and sells it to consumers or REEs. Legal advisors must understand that while EDC is a commercial entity, its strategic decisions are heavily influenced by the MME’s policy directives.

The Licensing Regime: A Granular Approach#

The Electricity Law mandates a strict licensing regime. The EAC issues various types of licenses, each defining a specific scope of activity. This granular approach allows for the coexistence of large state entities and small private operators within the same ecosystem.

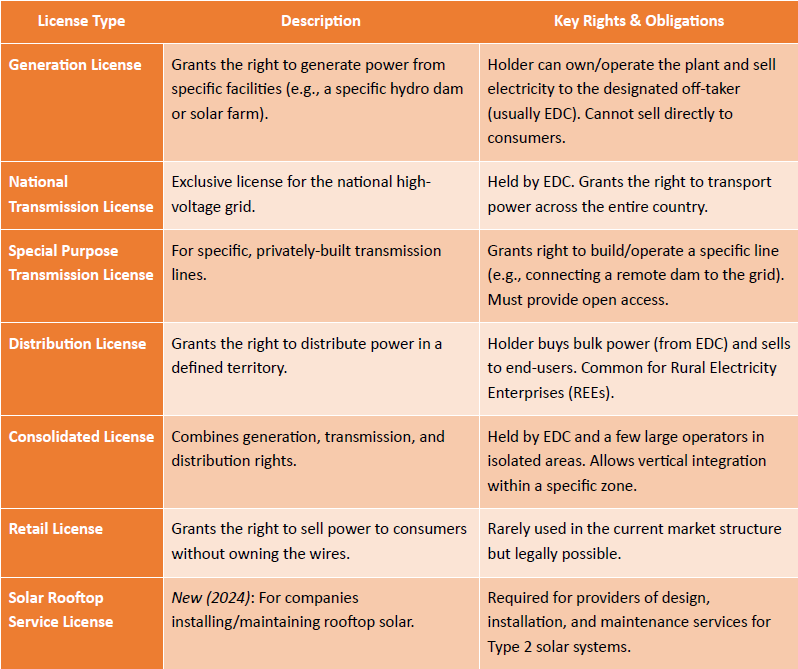

Table 1: Categories of Active Electricity Licenses in Cambodia

As of the end of 2024, the EAC had issued a total of 492 valid licenses. This includes 38 Generation Licenses, 12 Special Purpose Transmission Licenses, and a staggering 358 Distribution Licenses.2 The high number of distribution licenses reflects the historical legacy of the sector, where hundreds of small entrepreneurs (REEs) electrified rural Cambodia before the national grid reached them.

Market Structure: The Single Buyer Model#

Cambodia employs a Single Buyer Model (SBM). In this market design, EDC is the monopsonist—the sole purchaser of electricity from all independent generators and imports. It is also the monopoly supplier to distribution licensees and large consumers connected to the transmission grid.

The Commercial Flow of Energy#

The commercial relationship in the sector flows centrally through EDC:

Upstream (Generation): IPPs generate electricity and sell it to EDC under long-term Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs). There is no spot market; prices are fixed contractually.

Midstream (Transmission): EDC transports this power via the high-voltage National Grid. In some segments, private companies holding Special Purpose Transmission Licenses facilitate this transport for a “wheeling fee” paid by EDC.

Downstream (Distribution):

Urban Areas: EDC distributes power directly to consumers in Phnom Penh and provincial capitals.

Rural Areas: EDC sells power in bulk to REEs (Distribution Licensees) at a regulated wholesale tariff. The REEs then resell this power to rural households and businesses at a regulated retail tariff.

The Role of Independent Power Producers (IPPs)#

IPPs are the engines of generation growth in Cambodia. They operate under Build-Own-Operate (BOO) or Build-Own-Operate-Transfer (BOOT) schemes.

Contractual Security: The cornerstone of the IPP model in Cambodia is the PPA. These contracts typically feature a “Take-or-Pay” clause. This means EDC is obligated to pay for a minimum amount of energy (or available capacity) regardless of whether the grid actually needs that power at that moment.3

Bankability: This rigid structure shields investors from demand risk and market price volatility, making Cambodian energy projects highly “bankable” for international lenders. The PPA effectively guarantees the project’s revenue stream, assuming the plant is technically available to generate.

Key Players: The IPP landscape includes major international investors. For example, the Lower Sesan 2 Hydro project is a joint venture involving China’s Hydrolancang and Cambodia’s Royal Group. Similarly, solar projects involve players like SchneiTec and Sunseap.2

The Evolution of Rural Electricity Enterprises (REEs)#

REEs are a unique and critical component of Cambodia’s energy ecosystem. In the 1990s and early 2000s, when the state lacked the capital to extend the grid, local entrepreneurs obtained licenses to generate power (using small diesel gensets) and distribute it to their villages via low-voltage networks.

As the National Grid expanded, the regulator (EAC) mandated a transition. REEs were required to shut down their expensive, polluting diesel generators and connect to the EDC grid.

Current Status: Today, most REEs function solely as power distributors. They act as franchisees, maintaining the low-voltage network, metering customers, and collecting bills. They earn a margin—the difference between the bulk price they pay EDC and the retail price set by the EAC.4

Consolidation: The government encourages consolidation. Larger REEs are buying out smaller ones, or EDC is acquiring their assets, to improve efficiency and standardize service quality across the country.

Generation: Dynamics, Assets, and the Renewable Shift#

Cambodia’s generation mix has shifted dramatically from oil-dependence to a reliance on renewables and coal. As of 2024, the installed capacity stands at 5,044 MW, with a diverse portfolio of assets.2

Hydropower: The Seasonal Baseload#

Hydropower accounts for the largest share of generation, contributing approximately 46-50% of the total energy mix.

Key Assets: The 400 MW Lower Sesan 2 dam in Stung Treng is the flagship project. Other significant assets include the Kamchay (194 MW) and Stung Tatay (246 MW) dams.2

Implications: While hydro provides low-cost power (levelized costs often below $0.06/kWh), it introduces significant seasonality risk. During the dry season (roughly November to April), river flows decrease, reducing generation capacity. This forces Cambodia to rely on coal, imports, or solar to fill the gap.

Coal: The Controversial Backbone#

Coal-fired generation accounts for about 42% of the energy mix. It provides the firm, dispatchable baseload power needed to balance the intermittency of hydro and solar.

- Strategic Shift: Historically, Cambodia relied on coal for energy security. However, following China’s pledge to stop funding overseas coal projects and Cambodia’s own climate commitments, the PDP 2022-2040 places a moratorium on new coal projects. Existing projects (like those by CIIDG in Sihanoukville) remain operational, but planned expansions (e.g., Botum Sakor) have been cancelled or converted to LNG.5

Solar Power: The Rapid Ascent#

Solar energy has been the fastest-growing segment, reaching over 827 MW of capacity by 2024.6

Utility-Scale: The National Solar Park in Kampong Chhnang, supported by the ADB, pioneered the use of competitive auctions. This resulted in record-low tariffs (below $0.04/kWh), proving that solar could be cheaper than coal.7

Rooftop Solar: Distributed solar has exploded in popularity among factories seeking to lower costs and meet green targets. However, regulatory hurdles (discussed in Section 8) have historically constrained this growth.

Imports: The Balancing Act#

Despite achieving nominal self-sufficiency, Cambodia remains a net importer of electricity to ensure grid stability.

Sources: High-voltage imports come from Vietnam (via 230kV lines), Thailand (115kV), and Laos (specifically hydro imports).

Function: Imports are strategic. They act as a reserve margin during the dry season or when domestic plants undergo maintenance. The import contracts are government-to-government agreements managed by EDC.1

Transmission: The Nervous System of the Grid#

The transmission network is the physical manifestation of the single-buyer model. It is the infrastructure that allows EDC to move power from remote hydro dams in the northeast and coal plants on the coast to the load centers in Phnom Penh and Siem Reap.

Infrastructure Overview#

The National Grid operates primarily at 230kV and 115kV voltage levels.

Grid Loop: Major investments have closed the “loop” around the Tonle Sap lake and extended the backbone to the borders. By the end of 2024, this infrastructure enabled the grid to reach 99.99% of consumers.2

Substations: A network of Grid Substations (GS) steps down voltage for distribution. For instance, Phnom Penh is ringed by substations (GS1, GS2, GS3, etc.) that feed the capital’s hungry commercial sector.2

Special Purpose Transmission Licenses#

While EDC holds the National Transmission License, the law allows for private sector participation in transmission via Special Purpose Transmission Licenses.

Rationale: When EDC faces capital constraints or needs to accelerate a specific connection (e.g., linking a new remote dam to the grid), it can license a private company to build the line.

Regulatory Principles: The National Transmission Licensee (EDC) has the “first right of refusal.” If EDC cannot build the line within the required timeframe, the EAC can issue a license to a private entity.2

Case Study: (Cambodia) Power Transmission Lines Co., Ltd. (CPTL) holds a license to operate the 115kV line from the Thai border to Banteay Meanchey, Battambang, and Siem Reap. CPTL builds and maintains the line, and EDC pays a “wheeling charge” to use it. Importantly, the license mandates open access, meaning the licensee cannot block third-party power flows, subject to technical limits.2

The Tariff Regime: Procedures and Stability#

Electricity tariffs in Cambodia are not determined by market forces (supply and demand) as they are in wholesale markets. Instead, they are regulated administratively by the EAC based on the principle of “Reasonable Cost.”

Tariff Methodology#

The determination of tariffs follows a rigorous procedural framework outlined in the Procedures for Data Monitoring, Application, Review and Determination of Electricity Tariff.2

Cost-Plus Model: Tariffs are calculated to cover the licensee’s justifiable costs—operating expenses, fuel costs, depreciation, and finance costs—plus a reasonable return on equity.

Procedure B (Application): When a licensee (like an REE or EDC) wants to change their tariff, they must submit a detailed application to the EAC, including audited accounts and a rationale for the proposed rate.

Procedure C (Review): The EAC reviews the application, conducts public consultations (allowing consumers to comment), and holds a public hearing. The final decision is binding.2

Tariff Status in 2024#

Despite global volatility in fuel prices (coal and oil), the electricity tariff in Cambodia remained unchanged in 2024 compared to 2023.2

Subsidy: This stability was artificial, maintained through a massive government subsidy estimated in the “hundreds of millions of dollars.” The government absorbed the delta between high generation costs and the regulated retail price to protect the economy and citizens’ livelihoods.2

Strategic Plan: The government continues to implement a strategic plan to lower tariffs for industrial and agricultural consumers to boost competitiveness, though global inflation has temporarily stalled reductions.

Renewable Energy & Distributed Generation: The 2024/2025 Regulatory Pivot#

The most dynamic area of the Cambodian energy market is the regulation of rooftop solar and wind energy. After years of restrictive policies, 2024 and 2025 have seen a fundamental restructuring of the rules governing distributed generation.

Rooftop Solar: From Capacity Charges to Compensation Tariffs#

Historically, Cambodia imposed a hefty “Capacity Charge” on rooftop solar users. This was a monthly fee based on the installed capacity ($/kW/month) of the solar system, regardless of how much energy was actually consumed or generated.

In November 2024, the MME issued Prakas No. 0312, updating the principles for rooftop solar. This was followed by EAC regulations in 2025 that replaced the Capacity Charge with a more sophisticated Compensation Tariff mechanism.

System Classification#

The new framework categorizes rooftop solar systems into two types:

Type 1 (Isolated): Systems that are strictly off-grid and not synchronized with the national grid. These have minimal regulatory burdens.

Type 2 (Grid-Connected): Systems synchronized with the national grid. These are further sub-classified by size for 2024:

Small: ≤ 10 kWac.

Medium: > 10 kWac to 100 kWac.

Large: > 100 kWac.

The Quota System#

To manage the technical impact of variable solar energy on the grid, the government has introduced an annual Quota System.

2025 Quota: For the year 2025, the MME has authorized a total quota of 30 MW for new rooftop solar permits.2

Allocation: This quota is managed by the EAC and allocated on a first-come, first-served basis. This creates a competitive race for permits among factories and commercial buildings wishing to go green.

The Compensation Tariff#

The new “Compensation Tariff” is designed to be fairer than the old Capacity Charge. It is a variable fee paid on the energy consumed from the solar system, compensating EDC for providing standby power and grid stability services.

Calculation: The formula is complex but generally follows the logic: Compensation Fee = ( Solar Generation - 2 x BESS Discharge) x Rate

BESS Incentive: The formula explicitly incentivizes Battery Energy Storage Systems (BESS). If a user installs a battery and discharges at least 50% of their solar generation from it (effectively shifting load to peak hours or smoothing variability), the compensation fee can be waived or significantly reduced.

Rates: Preliminary rates for 2025 suggest medium systems pay ~$0.037/kWh and large systems pay ~$0.060/kWh on their self-consumed solar energy.

Wind Energy: Unlocking Mondulkiri#

Wind energy has lagged behind solar but is now accelerating. The province of Mondulkiri, with its high elevation and favorable wind speeds, is the epicenter of this development.

Projects: Two major projects are in advanced stages:

Challenges: Unlike solar, wind projects face significant land rights issues, particularly concerning indigenous communities and “spirit forests” in Mondulkiri. Legal due diligence on land titles and community consultations (FPIC) is critical here.10

Investment Climate and Project Finance#

For international investors, Cambodia offers a relatively open investment environment compared to its neighbors, underpinned by the Law on Investment (2021).

Incentives for Green Energy#

The 2021 Law designates renewable energy as a priority sector, eligible for “Qualified Investment Project” (QIP) status.11

Tax Breaks: QIPs can receive a corporate income tax holiday of 3 to 9 years.

Duty Exemptions: Investors can import construction materials, solar panels, and wind turbines duty-free.

Foreign Ownership: Crucially, Cambodia allows 100% foreign ownership in renewable energy projects. There is no requirement for a local partner, unlike in Thailand or Vietnam where restrictions often apply.11

Bankability of Contracts#

The “bankability” of Cambodian power projects is high, which has attracted financing from the ADB, IFC, and Chinese state banks.

Take-or-Pay: As noted, the standard PPA includes a Take-or-Pay clause. EDC pays for the capacity availability, mitigating the volume risk for the investor.

Currency: PPAs are often denominated in USD or have indexation clauses to protect against Riel depreciation.

Government Guarantee: Large IPPs are backed by an Implementation Agreement (IA) signed by the MME, which acts as a sovereign guarantee for EDC’s payment obligations.3

Comparative Analysis: Cambodia vs. Regional and Global Markets#

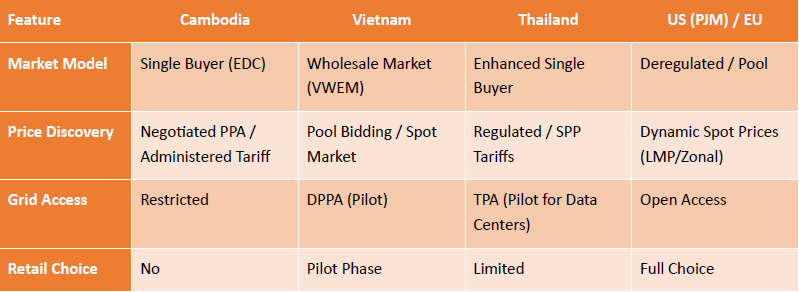

To understand the trajectory of Cambodia’s market, it is instructive to compare it with its peers and advanced markets.

Cambodia vs. Vietnam: The Move to Wholesale#

Vietnam: Has moved beyond the single buyer model to the Vietnam Wholesale Electricity Market (VWEM). Generators bid into a pool, and prices are determined by supply and demand. Vietnam has also piloted Direct Power Purchase Agreements (DPPA), allowing renewable generators to sell virtually or physically directly to large consumers (like Samsung) using the national grid.12

Cambodia: Remains a rigid Single Buyer. There is no wholesale pool. Direct sales from IPPs to consumers via the grid are strictly prohibited (except for the new specific rooftop licenses which are still self-consumption focused). Cambodia prioritizes the financial solvency of EDC over market competition.

Cambodia vs. Thailand: The Enhanced Single Buyer#

Thailand: Operates an “Enhanced Single Buyer” model. While EGAT is the central buyer, there is a well-established tier of Small Power Producers (SPPs) and Very Small Power Producers (VSPPs) with standardized PPAs. Thailand is also piloting Third Party Access (TPA) codes to allow green energy wheeling for data centers.13

Cambodia: Lacks the SPP/VSPP standardization. Every IPP is a bespoke negotiation. TPA is theoretically possible via Special Purpose Transmission Licenses but is not yet a regulatory reality for wheeling power to third parties.

Cambodia vs. US (PJM) / EU (Nord Pool)#

Structure: Advanced markets like PJM (USA) and Nord Pool (EU) are fully unbundled. The Transmission System Operator (TSO) is independent of market participants. Generation and retail are competitive. Prices are dynamic (Locational Marginal Pricing in PJM; Zonal Pricing in Nord Pool).14

Cambodia: EDC is vertically integrated (generation, transmission, distribution). There is no spot market. The philosophy is “planning and control” rather than “market efficiency.”

Table 2: Comparative Market Models

Dispute Resolution: Navigating Legal Risks#

The legal framework provides mechanisms for resolving disputes, but enforcement remains a complex area.

Administrative Resolution: The Electricity Law empowers the EAC to act as the first forum for disputes. It has a formal procedure involving complaint filing, reconciliation, and investigation. The EAC’s decisions are administrative but binding unless appealed.2

Judicial Appeal: Decisions by the EAC can be appealed to Cambodian courts within 3 months.

International Arbitration: Most foreign-invested PPAs stipulate international arbitration (e.g., Singapore International Arbitration Centre - SIAC). The landmark Cambodia Power Company case (ICSID Case No. ARB/09/18) is a critical precedent. In this case, the tribunal upheld jurisdiction over the Kingdom of Cambodia but dismissed claims against EDC due to a lack of specific designation. The case highlighted that while the government respects arbitration clauses, the corporate veil between the State and EDC can be a significant legal hurdle in enforcement.15

Conclusion#

The Cambodian energy market is a study in controlled evolution. The Royal Government has successfully utilized a rigid Single Buyer Model to drive massive infrastructure growth and achieve near-universal electrification. For investors, the market offers high stability through bankable, take-or-pay contracts and generous tax incentives.

However, the escalating global imperative to combat climate change, coupled with falling technology costs, is exerting considerable pressure on Cambodia’s traditionally centralized energy system to fundamentally adapt and integrate a greater share of renewable energy sources. This transition is not merely a technical challenge but a complex policy and regulatory balancing act. The 2024/2025 regulatory overhaul specifically targeting rooftop solar—a key area of rapid private sector adoption—serves as a primary illustration of this sophisticated policy effort.

This significant regulatory shift introduces both quotas and restructured compensation tariffs. The implementation of these quotas aims to manage the pace and scale of rooftop solar integration, ensuring grid stability is maintained while also preventing an overly rapid disruption to the existing power infrastructure. Simultaneously, the revised compensation tariffs represent a delicate attempt to find equilibrium: to incentivize the private sector and commercial enterprises to invest in green energy generation and meet their own sustainability goals, yet, critically, to also protect the state utility’s indispensable revenue base. The stability of the state utility is vital not only for continued grid operation and maintenance but also for financing large-scale national power infrastructure projects, including conventional generation and the necessary grid upgrades to eventually handle higher penetrations of intermittent renewables. This overhaul signifies a move toward a more managed, yet progressive, decentralization of the Kingdom’s energy generation.

For legal practitioners navigating Cambodia’s rapidly evolving energy sector, a deep and comprehensive understanding of several key regulatory and commercial areas is paramount. The fundamental task involves mastering the intricate nuances of the energy project licensing regime, which mandates meticulous adherence to various governmental approvals from the Ministry of Mines and Energy (MME) and the Council for the Development of Cambodia (CDC). This includes distinguishing between licenses for generation, transmission, and distribution, and understanding the requisite environmental and social impact assessments (ESIA) that often dictate project timelines.

Furthermore, the strict application of Cambodian land law represents a significant hurdle, especially for large-scale renewable energy projects such as wind and solar farms. Practitioners must navigate the distinctions between state public land, state private land, and private land, securing long-term leases or concessions that comply with the Land Law of 2001 and subsequent sub-decrees. Due diligence on land title, community engagement protocols, and securing the necessary permissions for transmission line right-of-ways are indispensable to de-risking these capital-intensive projects.

While Cambodia’s energy market structure currently differs from the fully liberalized, open markets seen in regional counterparts like Vietnam or developed Western economies—where wholesale markets, direct PPAs, and retail competition are common—the nation is on a decisive trajectory toward modernization. The government is actively refining its regulatory toolkit, updating its legal framework to enhance transparency, streamline bureaucratic processes, and offer better fiscal incentives. This regulatory evolution is explicitly designed to create a more attractive and secure investment climate, signaling Cambodia’s readiness to welcome the next, larger wave of sophisticated energy investment, particularly in utility-scale renewables and necessary grid infrastructure upgrades. The legal landscape is moving swiftly from a regime focused primarily on securing basic supply toward one that supports sustainability, competitive pricing, and complex grid integration.

Disclaimer: The information provided is for general informational purposes only and does not constitute legal advice. It is essential to seek the advice of a competent legal professional for your specific circumstances. Relying on this information without professional legal guidance is at your own risk.

Works cited#

Powering ASEAN’s Future: Energy Transition Challenges and Opportunities - Enerdata, accessed December 13, 2025, https://www.enerdata.net/publications/executive-briefing/asean-energy-connectivity.html ↩︎ ↩︎

EAC Annual Report on Power Sector for Year 2024, accessed December 13, 2025, https://eac.gov.kh/site/viewfile?param=annual_report%2Fenglish%2FAnnual-Report-2024-en.pdf&lang=en ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Energy Transition Initiative: Islands Playbook (Book) Phase 3 Sample: 10 Important Features of Bankable Power Purchase Agreement, accessed December 13, 2025, https://www.eere.energy.gov/etiplaybook/pdfs/phase3-sample-10-important-features.pdf ↩︎ ↩︎

Southeast Asia Energy Sector Development, Investment Planning and Capacity Building Facility National Electrification Efforts in Cambodia, accessed December 13, 2025, https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/project-documents/52096/52096-001-dpta-en.pdf ↩︎

Renewable Energy: The Top-Priority for Southeast Asia to Fully Blossom, accessed December 13, 2025, https://www.renewable-ei.org/pdfdownload/activities/REI_SEA2023_EN.pdf ↩︎

US firms urged to capitalise on Cambodia’s energy sector potential - Khmer Times, accessed December 13, 2025, https://www.khmertimeskh.com/501795377/us-firms-urged-to-capitalise-on-cambodias-energy-sector-potential/ ↩︎

from carbon to competition: cambodia’s transition to a clean energy development pathway - Climate Investment Funds (CIF), accessed December 13, 2025, https://www.cif.org/sites/cif_enc/files/knowledge-documents/summary_cif_gdi_case_study_cambodia_national_solar_park.pdf ↩︎

Cambodia to Commission First Wind Power Plant by 2026 - The Electricity Hub, accessed December 13, 2025, https://theelectricityhub.com/cambodia-to-commission-first-wind-power-plant-by-2026/ ↩︎

News - The Blue Circle, accessed December 13, 2025, https://www.thebluecircle.sg/news-tbc ↩︎

Cambodia: Chinese, Thai, Malaysian and Singaporean-invested wind farms spark Indigenous concerns over deforestation, farmland impacts and sacred sites, report says, accessed December 13, 2025, https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/latest-news/cambodia-chinese-thai-and-singaporean-invested-wind-farms-spark-indigenous-concerns-over-deforestation-farmland-impacts-and-sacred-sites-report-says/ ↩︎

2025 Cambodia Investment Climate Statement - State Department, accessed December 13, 2025, https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2025/09/638719_2025-Cambodia-Investment-Climate-Statement.pdf ↩︎ ↩︎

Investing in Renewable Energy: How Decree 57 Reshapes Vietnam’s Regulatory Framework, accessed December 13, 2025, https://www.vietnam-briefing.com/news/vietnam-renewable-energy-decree-57.html/ ↩︎

Thailand’s Draft Third-Party Access (TPA) Code 2025: Legal Framework, Direct PPA Pilot for Data Centers, and Comparative Insights - Formichella & Sritawat - Attorneys at Law, accessed December 13, 2025, https://fosrlaw.com/2025/thailand-third-party-access-code-2025/ ↩︎

Understanding the Differences Among PJM’s Markets, accessed December 13, 2025, https://www.pjm.com/-/media/DotCom/about-pjm/newsroom/fact-sheets/understanding-the-difference-among-pjms-markets.pdf ↩︎

Cambodia Power Company v Kingdom of Cambodia - ICSID Case No. ARB/09/18 - Award of the Tribunal - 22 April 2013 - Legal & Regulatory docs. - Transnational Dispute Management, accessed December 13, 2025, https://www.transnational-dispute-management.com/legal-and-regulatory-detail.asp?key=34313 ↩︎