Cambodia’s Internet Infrastructure: From Reliance to Global Connectivity

Table of Contents

Cambodia has embarked on a transformative journey to achieve digital autonomy, moving from a historical dependence on neighboring countries, particularly Thailand and Vietnam, for its internet bandwidth to establishing direct, independent connections to the global internet backbone. This strategic pivot, culminating in the recent cessation of internet purchases from Thailand, is the result of years of concerted infrastructure investment and policy initiatives.

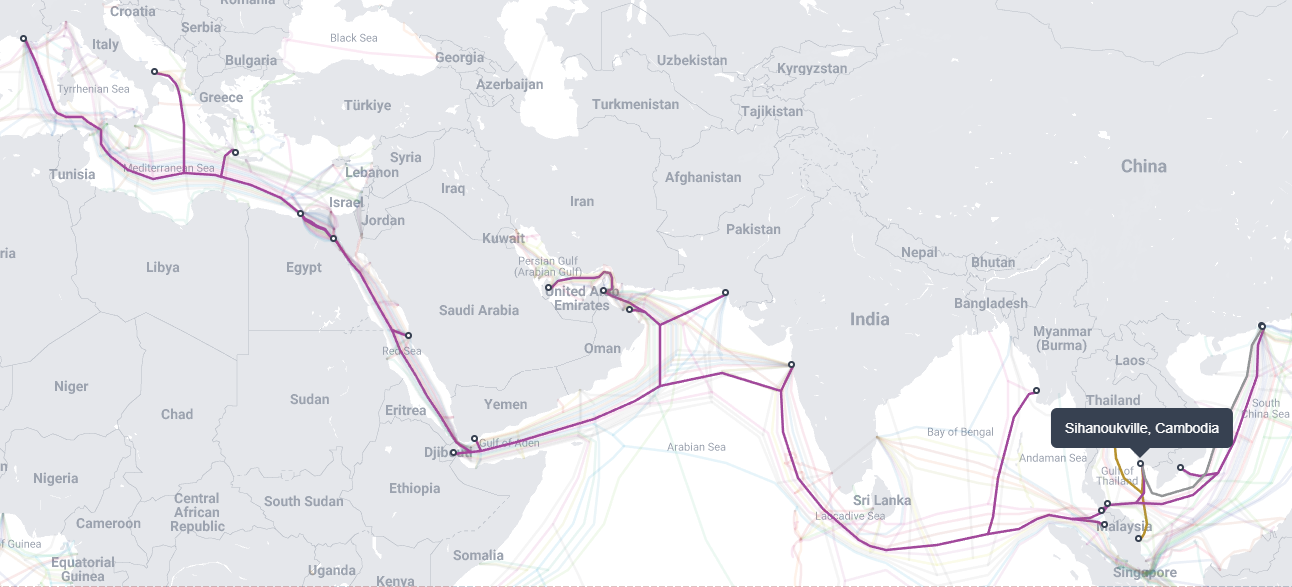

Key milestones, such as the operationalization of the Malaysia-Cambodia-Thailand (MCT) and Asia-Africa-Europe-1 (AAE-1) submarine cables, and the impending completion of the Sihanoukville-Hong Kong (SHV-HK) cable, underscore this shift. This post explores Cambodia’s evolution towards digital self-sufficiency, exploring the geopolitical drivers, infrastructure development, economic implications, and ongoing challenges that define its path to a more resilient and sovereign digital future.

1. Introduction: From Reliance to Resilience#

For many years, Cambodia’s connection to the global internet backbone was akin to a town that relied on a single, often congested, road through a neighboring country to access the main highway of commerce and communication. This single road, primarily through Thailand and Vietnam, made Cambodia vulnerable to external factors and limited its digital potential. Historically, international bandwidth for Cambodia predominantly transited through terrestrial links via its neighbors, specifically Thailand and Vietnam.1 This meant that a significant portion of Cambodia’s digital traffic had to physically traverse another country’s infrastructure before reaching the broader global internet.1 This reliance on external transit points, a legacy from the early days of dial-up internet, presented a fundamental constraint on Cambodia’s digital development.2

This historical dependence was not merely an economic bottleneck or a technical inconvenience; it represented a strategic vulnerability. The implications of such reliance became acutely evident with recent geopolitical developments. On June 12, 2025, Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Manet declared that Cambodia would cease purchasing internet and electricity from Thailand.3 This decisive action was directly linked to rising border tensions and specific threats from extremist groups in Thailand to disrupt internet and electricity supplies to Cambodia.4 The Prime Minister’s statement emphasized that this proactive measure was taken “in order to avoid delays or complications for the Thai side in deciding whether or when to cut the supply”.5 This immediate trigger, rooted in national security and sovereignty concerns, underscores that the long-term pursuit of direct connectivity is deeply intertwined with broader state resilience. The previous reliance on a single, external pathway was a strategic weakness, making the investment in independent infrastructure a critical national imperative to prevent external leverage. This elevates the discussion from mere infrastructure development to a matter of national self-determination in the digital realm. This section sets the stage for understanding Cambodia’s multi-year preparation to achieve digital independence, transforming its “single road” into multiple, direct digital highways.

2. The Early Digital Landscape and Initial Dependencies#

Cambodia’s First Steps Online (1997-Early 2000s)#

Cambodia first entered the internet era in May 1997, marking the beginning of its digital journey. The inaugural internet service, Camnet, was operated by the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications (MPTC) with support from the International Development Research Centre of Canada.6 Initial international connectivity was established through a modest 64 Kilobytes per second (kbps) satellite link to Singapore.6 This early infrastructure was limited, serving only about 90 users initially, primarily government ministries, universities, and NGOs, with a heavily subsidized service.6 Commercial internet services soon followed, with Australia’s Telstra launching “Big Pond” in June 1997, creating early competition.6

However, internet access remained a luxury. In 2001, the cost of internet service was approximately $3.33 per hour for prepaid cards from providers like Camnet.6 Connectivity was largely confined to urban centers such as Phnom Penh and Siem Reap, where a few internet cafes provided the primary public access, with remote areas remaining largely disconnected.6 This nascent stage highlighted the significant barriers to widespread adoption, primarily due to high costs and limited infrastructure.

The Reality of Terrestrial Transit: Reliance on Neighbors#

As internet usage gradually expanded, Cambodia’s international bandwidth continued to largely transit through land-based fiber connections via Thailand and Vietnam.1 This meant that Cambodia’s internet traffic was inherently subject to the infrastructure, policies, and potential disruptions within these transit countries.1 This arrangement, while providing necessary connectivity, inherently limited Cambodia’s digital autonomy and exposed it to external influences.

A notable transformation in the telecommunications sector occurred over the subsequent years. While internet access in 2001 was prohibitively expensive, by 2018, telecommunication costs in Cambodia had become “the cheapest in ASEAN”.7 This dramatic reduction in cost, driven by increased competition among providers and growing infrastructure, was a foundational development, shifting internet access from a luxury to a more widely accessible utility. However, this affordability did not immediately translate into high-capacity, high-quality internet for all users. For instance, in 2016, Cambodia’s international internet bandwidth per user was only 16.31 kbps, significantly lower than the world average of 151.10 kbps.8 This disparity revealed a critical nuance: while efforts succeeded in making internet access more affordable, the underlying international bandwidth capacity remained a bottleneck for more data-intensive applications and a truly robust digital experience. This situation underscored the ongoing need for substantial bandwidth upgrades, which subsequent infrastructure projects aimed to address.

3. Building the Digital Backbone: Years of Preparation#

Domestic Fiber Optic Network Development#

The foundation for Cambodia’s digital independence was laid through significant efforts to build a robust national fiber optic backbone. The Cambodia Fibre Optic Communication Network Company (CFOCN), established in 2006, secured a 35-year license in 2007 from the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications to implement and maintain the National Information Highway Fiber Optic Network Project.9 This ambitious project involved the construction of approximately 2,000 km of fiber optic backbone network across the country, implemented in two phases between 2014 and 2015.9

This foundational infrastructure development was significantly bolstered by foreign investment, primarily from China. China Eximbank provided a $50 million buyer’s credit loan to CFOCN, with additional loans from other Chinese banks such as ICBC and China Development Bank (CDB).9 Furthermore, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) approved $75 million in 2019 to support the development of both the fiber backbone and metro networks, aiming to increase access to telecom services in both rural and urban areas and provide greater capacity for operators.10

The First Submarine Cables: MCT and AAE-1 Cables#

A pivotal strategic shift occurred with the deployment of Cambodia’s first direct undersea cables, moving beyond exclusive reliance on terrestrial transit through its neighbors. The Malaysia-Cambodia-Thailand (MCT) cable, Cambodia’s first submarine cable, officially launched in March 2017.1 This 1,300-kilometer cable connected the three countries to the existing Asia-America Gateway (AAG) system, providing a direct link from Southeast Asia to the United States.2 The MCT cable, a collaborative project involving Telcotech (a subsidiary of local internet provider Ezecom), Telekom Malaysia, and Symphony Communication of Thailand, and built by Huawei Marine Networks, offered a crucial solution for Cambodia’s growing connectivity needs, significantly reducing its dependence on terrestrial links.2

Following closely, Cambodia also became involved in the Asia-Africa-Europe-1 (AAE-1) submarine cable, which became operational in July 2017.11 This extensive 25,000 km cable system connects Hong Kong, Vietnam, Cambodia, and other countries across Asia, Africa, and Europe.12 The AAE-1 cable system, designed with 100Gbps technology and a trunk capacity of over 40 Tbps, provided additional capacity and critical redundancy towards global hubs like Hong Kong and Singapore, and onwards to Europe and the Middle East.11 This foresightful investment in undersea infrastructure provided vital redundancy and increased bandwidth, laying the groundwork for the eventual ability to reduce reliance on terrestrial connections through Thailand without catastrophic service collapse.

The Sihanoukville-Hong Kong (SHV-HK) Submarine Cable: A Game Changer#

A significant leap towards greater digital independence for Cambodia is embodied by the Sihanoukville-Hong Kong (SHV-HK) Submarine Cable. This nearly 3,000-kilometer high-capacity cable is designed to run directly from Hong Kong to Sihanoukville in southern Cambodia.1 The project, initially planned for 2024, is now anticipated to be completed by July 2025, with installation works in Hong Kong waters tentatively scheduled to commence in the third quarter of 2025.13

This cable represents a substantial investment of $165 million and involves China’s Unicom Group as a key partner.11 Its purpose is to replace older links and add significant undersea fiber capacity within Cambodia’s territory, promising faster and more affordable internet service.1 The decision to cease internet purchases from Thailand in June 2025 — just ahead of the SHV-HK cable’s scheduled completion in July — suggests that the Cambodian government was confident in its impending independent capacity, the result of years of strategic infrastructure planning.

Source: Cambodia’s Submarine Cable Map

Table 1: Key Milestones in Cambodia’s Internet Infrastructure Development (1997-Present)

| Year | Event/Cable Name | Type of Connectivity | Partners/Operators | Strategic Importance/Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997 | First Internet Connection (Camnet) | 64 kbps Satellite Link | Ministry of Post and Telecommunications (MPTC) | Initial gateway to global internet, high cost, limited access6 |

| 2014-2015 | National Information Highway Fiber Optic Network | Domestic Terrestrial Fiber | CFOCN, China Eximbank, ICBC, CDB, AIIB | Foundation for nationwide connectivity, internal backbone development9 |

| 2017 (March) | Malaysia-Cambodia-Thailand (MCT) Cable | Submarine Fiber Optic | Telcotech (Ezecom), Telekom Malaysia, Symphony Comm. of Thailand | First direct undersea cable, diversifying international bandwidth, reducing terrestrial reliance1 |

| 2017 (July) | Asia-Africa-Europe-1 (AAE-1) Cable | Submarine Fiber Optic | CFOCN (Cambodia part), Multi-country consortium | Additional capacity and redundancy to Europe/Middle East/HK11 |

| 2025 (July est.) | Sihanoukville-Hong Kong (SHV-HK) Cable | Submarine Fiber Optic | Cambodia Telecom, China Unicom | Major direct high-capacity link to global backbone, significantly reduces regional transit reliance, enhances digital sovereignty1 |

4. Navigating Challenges and the Path Forward#

Addressing the Digital Divide (Urban-Rural Disparities, Affordability, Literacy)#

Despite significant strides in overall internet penetration and connectivity, a persistent digital divide remains a considerable challenge for Cambodia. Urban centers generally enjoy robust connectivity, but rural regions continue to grapple with limited internet access and often unreliable electricity supply.1 This disparity is evident in infrastructure gaps, where large swathes of the countryside lack fiber backhaul and rely on less stable mobile networks or older 3G signals.1

Affordability also continues to be a hurdle. While mobile data has become relatively cheaper (approximately $0.42 per GB in 2022), fixed broadband remains expensive relative to the average income. For instance, a fixed broadband subscription cost about $28 per month in 2023, a substantial sum when compared to the minimum monthly wage of around $194.1 This cost barrier limits widespread access, particularly for the 15% of Cambodians living below the poverty line.1

Furthermore, low technological literacy is a significant barrier, hindering a considerable portion of the population from effectively engaging with digital services, even where access is available.11 These “last mile” challenges, encompassing infrastructure gaps, affordability, and digital literacy, remain critical impediments to achieving true digital equity. Without robust funding and policy backing for rural internet projects, the full potential of a connected Cambodia, including its digital economy, will remain unrealized for a significant portion of its population, potentially exacerbating existing inequalities. This is a crucial area for future policy focus to ensure that the benefits of digital transformation are truly inclusive.

Sustaining Growth and Ensuring Redundancy#

To sustain its digital growth and maintain competitiveness, Cambodia must continue to invest significantly in its internet infrastructure. This includes the full rollout of 5G networks, which are currently in trial phases14, and the ongoing expansion of its fiber optic network. Meeting the escalating demand for data and ensuring high-quality connectivity will necessitate continuous upgrades and expansion.

Furthermore, while the new SHV-HK cable significantly enhances direct international connectivity, it is crucial for Cambodia to continue diversifying its international connections. A robust and resilient strategy should follow a “3-2-1” redundancy model: three independent submarine cables to ensure oceanic redundancy, two low-earth orbit (LEO) satellite links to maintain service in case of undersea disruptions, and one terrestrial cross-border cable to provide an overland alternative route. This layered approach would help safeguard against single points of failure, ensuring uninterrupted connectivity even in the face of geopolitical tension, natural disasters, or infrastructure faults. Continued public-private partnerships and foreign investment will be essential drivers for future expansion and the realization of Cambodia’s ambitious digital transformation goals.15

5. Conclusion: A Connected Future#

Cambodia has embarked on a remarkable journey, transforming from a digitally isolated nation heavily reliant on its neighbors for internet access to one actively building a robust, independent, and diversified digital infrastructure. This transition marks a significant step towards enhanced national resilience and sovereignty. The analogy of moving from a single, vulnerable road to multiple, direct digital highways aptly captures this strategic shift, highlighting Cambodia’s proactive and long-term preparation.

The strategic investments in domestic fiber networks, such as the National Information Highway, and pivotal undersea cables like MCT, AAE-1, and the upcoming SHV-HK, have fundamentally reshaped Cambodia’s connectivity landscape. These efforts, often bolstered by significant foreign partnerships, have enabled the nation to assert greater control over its digital destiny, as demonstrated by the recent cessation of internet purchases from Thailand amidst geopolitical tensions.

The implications of this digital transformation are profound, fueling the growth of Cambodia’s digital economy across e-commerce, fintech, and other sectors, and promising substantial job creation and broader societal benefits. However, the path forward is not without its complexities. Persistent challenges such as the urban-rural digital divide, affordability issues, and digital literacy gaps must be addressed to ensure equitable access for all citizens.

The future of Cambodia’s digital landscape will depend on its ability to successfully balance these competing priorities. By continuing to invest in inclusive infrastructure, fostering digital literacy, and navigating regulatory frameworks that promote both security and freedom, Cambodia is poised to realize the immense potential of a truly connected and equitable future for all its citizens.

Works cited#

Cambodia’s Internet Boom or Digital Doom? Inside the Kingdom’s Connected Revolution, accessed June 14, 2025, https://ts2.tech/en/cambodias-internet-boom-or-digital-doom-inside-the-kingdoms-connected-revolution/ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

First submarine cable launched - Open Development Mekong, accessed June 14, 2025, https://opendevelopmentmekong.net/news/first-submarine-cable-launched/ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Cambodia to end reliance on Thai electricity and internet amidst border tensions, accessed June 14, 2025, https://www.pattayamail.com/thailandnews/cambodia-to-end-reliance-on-thai-electricity-and-internet-amidst-border-tensions-505090 ↩︎

Cambodia Cuts Thai Internet, Bans Entertainment, Affirms Power Independence, accessed June 14, 2025, https://laotiantimes.com/2025/06/13/cambodia-cuts-thai-internet-bans-entertainment-affirms-power-independence/ ↩︎

Cambodia ends internet bandwidth purchases from Thailand amid extremist threats: PM Hun Manet (VIDEO) - Khmer Times, accessed June 14, 2025, https://www.khmertimeskh.com/501699477/cambodia-ends-internet-bandwidth-purchases-from-thailand-amid-extremist-threats-pm-hun-manet/ ↩︎

The Origins of the Internet – YIGF Cambodia, accessed June 14, 2025, https://yigfkh.org/the-origins-of-the-internet-en/ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Chea Serey - Wikipedia, accessed June 14, 2025, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chea_Serey ↩︎

Cambodia Internet bandwidth - data, chart | TheGlobalEconomy.com, accessed June 14, 2025, https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/Cambodia/Internet_bandwidth/ ↩︎

ICBC provides $15 million loan for National Information Highway Fiber Optic Network Project (Linked to Project ID#85323, #85328, #85330, #85333, #85335, #85339) - China AidData, accessed June 14, 2025, https://china.aiddata.org/projects/85329/ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Cambodia: Fiber Optic Communication Network Project - AIIB, accessed June 14, 2025, https://www.aiib.org/en/projects/details/2019/approved/Cambodia-Fiber-Optic-Communication-Network-Project.html ↩︎

Chinese involvement in Cambodia’s internet infrastructure (English) - Mekong, accessed June 14, 2025, https://data.opendevelopmentmekong.net/dataset/68b8ab29-29e2-42e1-bf9b-72f8cc7b7018/resource/90e851e3-03c5-424e-b6d1-9f73ab1dafaa ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

AAE-1 Fault Repairs Not Anticipated Until November - SubTel Forum, accessed June 14, 2025, https://subtelforum.com/aae-1-fault-repairs-not-anticipated-until-november/ ↩︎

Sihanoukville-HK Submarine Cable Completion in 2025 - SubTel Forum, accessed June 14, 2025, https://subtelforum.com/sihanoukville-hk-submarine-cable-completion-in-2025/ ↩︎

Internet Infrastructure in Cambodia: 2025 Outlook - Loma Technology, accessed June 14, 2025, https://lomatechnology.com/blog/internet-infrastructure-in-cambodia-2025-outlook/3148 ↩︎

Push to ensure universal mobile service coverage by 2027 - Khmer Times, accessed June 14, 2025, https://www.khmertimeskh.com/501635256/push-to-ensure-universal-mobile-service-coverage-by-2027/ ↩︎